Charles Fort

Based on “The Military and institutional Occupations of Charles Fort, St. Kitts, West Indies” by Gerald Schroedl and Todd M Ahlman in Historical Archaeologies of the Caribbean: Contextualizing Sites through Colonialism, Capitalism and Globalism edited by Todd M Ahlman and Gerald F Schroedl (Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 2020)

The Second Anglo-Dutch war was fought between 1665 and 1667. France became involved as it had a defensive alliance with Holland. In St. Kitts where the English and the French continued to share the island, the French attacked British fortifications and plantations. When the war was over, the island returned to being a shared space. The English dismantled their damaged gun placements near the northern French boundary and around 1674 started constructing Charles Fort to guard Sandy Point which was, by then, their main trading port. The Fort covered 4.2 acres and was surrounded by a defensive ditch. It was mostly completed by the late 1680s but the five bastions were still under construction in the 1730s. Enslaved labourers from the plantations constructed it, maintained it and repaired it especially after the numerous battles and invasions that were fought on the island in its first 100 years of colonisation..

During the French invasion of 1689, Col Thomas Hill and 400 men were able to hold out there until they surrendered six weeks later. The English retook the fort in less than a week, the following year, by using cannon fire from Brimstone Hill. This short but intense siege caused the destruction of numerous houses with the grounds of Charles Fort. The ruinous French invasion of 1706 also caused damage to the fort and the structures within it. In 1724, the fort was armed with 27 canons. The compound contained a store house, guardhouse, barracks and officers’ quarters, prison, arsenal and magazine, a stone kitchen and two ovens. In 1779, a proposal was made to build a hospital, a blacksmith shop and a shade for the carpenter’s shop. It could hold from 30 to 100 men.

Charles Fort continued to be maintained for a while after the French invasion of 1782 but by then most of the resources were being applied to Brimstone Hill. In 1838, it was reported that all fortifications around the Island with the exception of the Hill were in ruins. New uses were considered for Charles Fort. In 1839 consideration was given to turning it into a poor house, then a lunatic asylum in 1846 and in 1854 it was to be turned into a lazaretto.

The Lazaretto finally materialised in 1890. As a result, the fort was laid out in four distinct areas - administration and food preparation, treatment, separate housing for male and female patients, and a cemetery and church. It was estimated that 100 patients could be accommodated. Men outnumbered women. Patients housing consisted of prefabricated housing imported from the US. The grounds were landscaped and fenced. In 1926, a wooden assembly or recreation area was built. Male and female patient interaction was again restricted within this structure. Here patients could listen to radio and later watch television. They could also grow vegetables and tend flower beds. As health services improved and more medicine became available, the number of patients declined. Following the introduction of universal suffrage in 1952, the leper home in Charles Fort had its own polling station. The institution was finally closed in 1996.

In 2012 Charles Fort was vested in the St. Christopher National Trust and is currently managed by the Brimstone Hill Society and National Park on behalf of the Trust.

Lawyer Stephen's Cave

by Alex Robinson

According to the oral tradition the cave was first fashioned by maroons out of the side of Olivees Mountain in the 17th century. In a series of local history programmes a contemporary griot, Tamboura Kitwana, from St. Kitts Ministry of Culture, described the site:

“The cave is made of packed earth and rock, with a smoke hole and a door sized opening at the back, and is surrounded by gullies to the east, west and south. There is a path above the cave which leads straight up to the top of the ridge, over Olivees Mountain to Cayon.” Standing in the middle of the rain forest, about eighty feet below the cave, is a plunge bath made of dressed stone, reputed to have been built by Stephen.

James Stephen was a barrister in St Kitts 1783-1794; according to the oral tradition, he counselled enslaved Africans and free Blacks to pursue their rights. Following a series of prosecutions which aimed to curtail the rights of slaveholders’ use of brutal punishments, he alienated the white community to such a degree that he withdrew to the hills and took refuge in a cave. There, he continued to advise the enslaved workers and wrote reports on conditions, which he sent secretly to the Abolition Committee in London.

The oral tradition is supported by the evidence of these prosecutions , particularly the celebrated Herbert case: William Herbert, a local merchant, was accused of gross cruelty “upon one Billy, a Negro child of the age of Six Years, [...] that he did gag inhumanely and immoderately, wantonly and cruelly […] beat, wound, bruise and ill-treat the child so that of his life was greatly despaired.” The guilty verdict was without precedent in the English speaking Caribbean and caused bitter recrimination on the island.

Stephen’s visit to England and his meeting with Wilberforce on January 31, 1789 is also recorded: he met Wilberforce in Palace Yard and agreed to report to him.

Stephen returned to England in 1794, supporting the Haiti revolution and too radical for Wilberforce, but he learned to temper his radicalism. It was his strategy that led to the Orders in Council of 1806 which banned the slave trade to Britain’s enemies, making way for the Act abolishing the slave trade altogether in 1807, which he drafted. He spent the rest of his life campaigning for an end to slavery, as an MP from 1808 – 1815, as a founding member of the African Institution and author of a two volume, thousand page study, The Slavery of the British West Indian Colonies Delineated[…]. Stephen’s interpretation of plantation slavery is unique and prescient; he draws from close observation of the system and presents the horrors and excesses of that system, not as exceptions, but as commonplace, and perhaps most chilling, as sanctioned by law. Some of these observations were first reported in this cave, and the story preserved in the oral tradition affords agency to the island of St. Kitts in the achievement of Abolition.

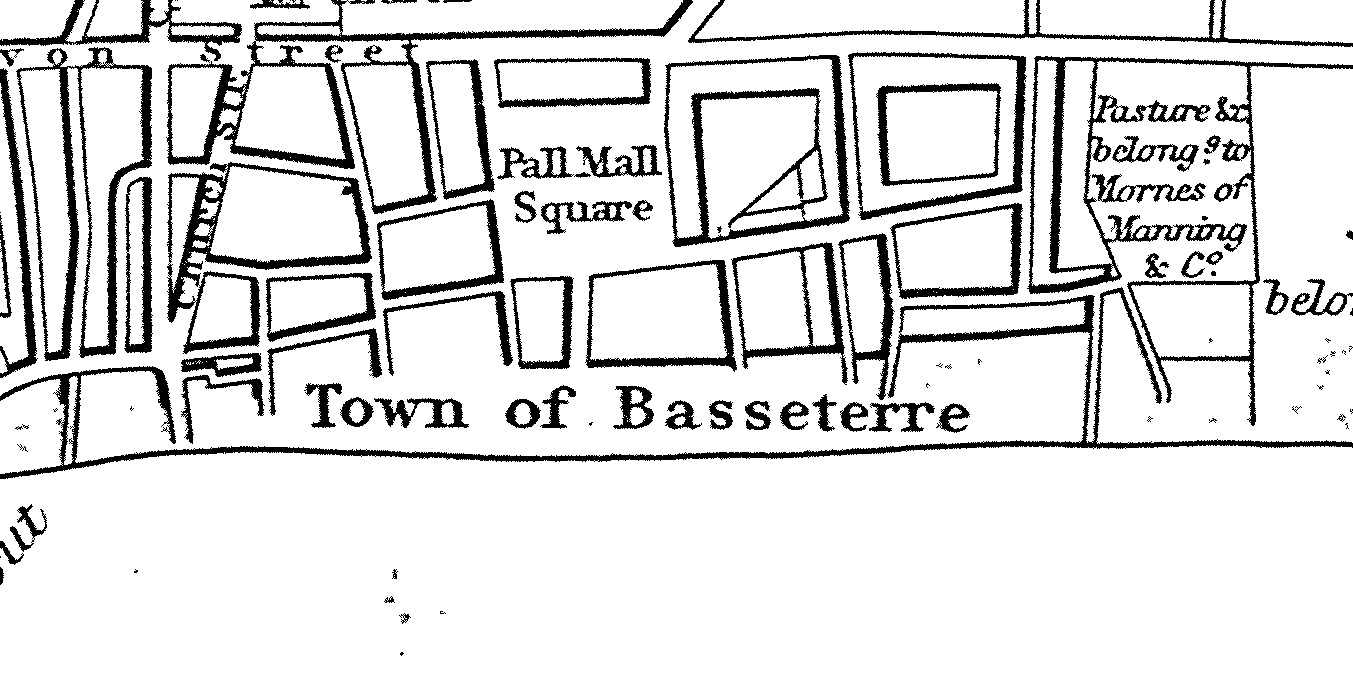

Bank Street

The Road heading east from the Circus is Bank Street. A bank has been at its southern corner where it meets Fort Street for almost 200 years. The first one was probably Colonial Bank which was set up by Royal Charter in 1836 to trade in the West Indies.

The former enslavers had been given £20 million as compensation for the loss of their unpaid labour. This meant that there was a significant increase in the money supply both in Britain and the colonies. Entrepreneurs started to realise that it would be good business to establish a bank. Planters and their merchant bankers in London were also aware that when the Apprenticeship system came to an end they would have to pay in cash for the labour on the estates.

Offices of Colonial Bank opened in the West Indies on the 15 July 1837. Despite the ups and downs of the sugar industry in the region, the Bank survived and in the early 20th century was allowed to extend its operations to other part of the world. In 1925 by Act of Parliament, Colonial Bank changed its name to Barclays Bank (Dominion, Colonial and Overseas) and it started operating as a private subsidiary of Barclays Bank Ltd. In 2002 Barclays took the name of First Caribbean and merged its operation with The Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. Barclays has since withdrawn from the region but First Caribbean continues to operate here.

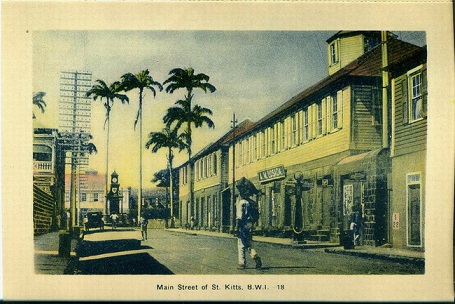

Liverpool Row

Liverpool Row stretches in the opposite direction from Bank Street. It heads West from the Circus. It is not clear if this street actually existed in French times. If it did, it would not have been known by its current name.

Liverpool Row was the commercial centre of Basseterre. This was where most merchants set up business. If they did not own a plantation house, they would have lived above their store front. Slave trading would have taken place here as often merchants preferred to deal out of their own premises. The street was an ideal location as it is close to the Bay Front, where their goods were landed. Its name is a testament to the close commercial relationship that existed between Liverpool in the England and the island’s merchant class.

The area past Church Street, where Fort Thomas Road starts, would have housed their porters and domestic servants. In the years after Emancipation in 1834, this part of Basseterre was a magnet for those who were looking for a life away from the cane fields.

Fort Street

National Archives

Government Headquarters

Church Street

Basseterre

St. Kitts, West Indies

Tel: 869-467-1422 | 869-467-1208

Email: NationalArchives@gov.kn

Website: www.nationalarchives.gov.kn

Follow Us on Instagram