Part 1

by Cameron St. Pierre Gill

The town of Sandy Point was the first major seaport on the island of St. Christopher (St. Kitts), the earliest English colony in the British West Indies. Many mistakenly claim that Sandy Point was St. Kitts first English town. This is not so, that honour belongs to Old Road, the site of Thomas Warner’s first settlement. When St. Kitts was divided between the English and French, Old Road was the administrative capital of St. Christopher (English St. Kitts) and Sandy Point was the trading centre, while Basseterre was the capital of St. Christophe (French St. Kitts).

Barry Higman has noted that the export driven plantation economy which became a feature of many Caribbean islands first emerged in the Leeward Islands. Early ports such as Sandy Point were indispensable to the growth of that burgeoning export driven plantation economy. As the first major English port town in the Eastern Caribbean Sandy Point became important not only to England's claim on St. Kitts but to her ambitions on the other islands as well. Unlike the other English and French towns on the island, namely Old Road, Basseterre and Cayon, Sandy Point was located next to one of the two boundaries that separated the English and French settlements, whose relationships with each other was always hostile, frequently erupting into armed conflict. The fact that the northern boundary between St. Christophe and St. Christopher ran through the bay at Sandy Point only contributed further to the hostile state of affairs. The Sandy Point Anchorage is one of the largest in the Eastern Caribbean, comparable in size to the anchorages at Basseterre, Oranjested in St. Eustatius, Prince Rupert's Bay in Dominica, Carlisle Bay and Speightstown Anchorage in Barbados. The size of the Sandy Point Anchorage and its location on a contested boundary between two rival European powers caused this anchorage to assume huge strategic importance.

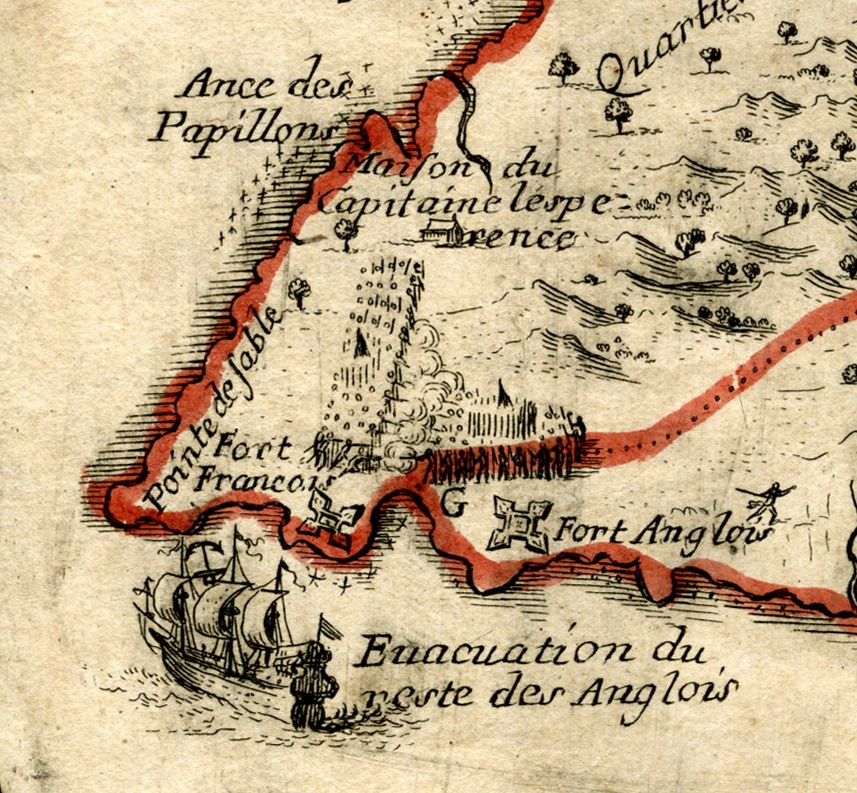

Consequently, within the first century of the island’s settlement the Sandy Point Anchorage became heavily fortified at both ends. The French erected a fortress on the northern bluff of the anchorage (where the village of Fig Tree is located), which is depicted on Etienne Vuillemont’s 1667 Map as “Fort François”. On the opposite (southern) end the English erected Charles Fort, named after King Charles II who had taken the almost unheard of step of financing the fort’s construction out of his own pocket. The King’s actions were indicative of the importance of St. Kitts and more specifically, the importance of the fledgling border town of Sandy Point and its anchorage to Britain's imperial ambitions. After St. Kitts came completely under English control in 1713, Fort François became Fort Charles, a name that still causes some confusion because of the similarly named fort at the other end of the bay.

With respect to that other fort, Charles Fort would begin life as a fort that differed from other early Caribbean forts, including even its younger and now more famous sister, the Brimstone Hill Fortress. Most of the region’s forts began life as simple fortified artillery positions which over time were extended and improved, eventually evolving in some cases into major fortresses. Some notable examples are the Cabrits in Dominica, the aforementioned Brimstone Hill, Fort Delgres in Guadeloupe, and El Morro and San Cristobal in Puerto Rico. Charles Fort, on the other hand, was conceived from the beginning as a comprehensive masonry fortress. There was no haphazard planning in its construction, all of the gun positions are connected by curtain walls that fully enclose the fort, remarkable for a mid to late seventeenth century Caribbean fortification!.

What is equally remarkable is that it took approximately eleven years to complete what would be one of the largest coastal fortresses in the Eastern Caribbean. When one considers that funding for defence works was often a contentious issue between Crown and colonies, such a commitment is impressive. However, all the King’s horses, money and English men could not have made Charles Fort a reality without enslaved African labour. These anonymous labourers and stonemasons have left as testament to their endurance and skill perhaps the oldest surviving intact and original seventeenth century masonry fortification in the Caribbean, a fort built originally in stonework when most other buildings in the Caribbean of the time were being hewn from timber.

Impressive as Sandy Point’s principal coastal fortification was, Charles Fort had one weakness that afflicted, regardless of their size, all coastal fortifications, vulnerability to naval gunfire and encirclement by enemy troops landing on the coast out of range of its guns. However, the limitations in artillery technology of the time meant that in order for their guns to have reasonable range out to sea and properly cover a bay they had to be sited directly on the coast. In 1690, during one of the many armed conflicts between the English and French on St. Kitts, Charles Fort was overrun by the French. The English with the assistance of enslaved Africans dragged guns up Brimstone Hill (which at the time was a limestone quarry) to fire onto the occupied Charles Fort. The artillery fire from Brimstone Hill succeeded in routing the French from Charles Fort and opened English eyes to the utility of Brimstone Hill as firing position. It was from then that fortifications began to be erected atop Brimstone Hill, initially for the purpose of providing a backup defence for Charles Fort. By the mid eighteenth century advances in artillery technology permitted guns located slightly further inland to adequately cover a stretch of coastline and the waters off it. Such progress enabled Brimstone Hill to come into its own, superseding Charles Fort as the primary defence of the Sandy Point Anchorage, although the latter remained an important defensive position up to the late nineteenth century.

While we can pinpoint the dates at which construction of Sandy Point’s major fortifications began and the dates of the first English and French settlements on St. Kitts, much more elusive is the date of the town of Sandy Point’s founding. Early map references to “Sandy Point” refer to a natural geographic feature, the expansive sandy bluff also known as Belle Tete (Pretty Head), not a town. However, a document from the sixteenth century offers a tantalizing clue of at least the period by which the town was already in existence. The Bibliotheque Nationale (National Library) in Paris, France contains a book published in 1667 titled Histoire general des Antilles par les François. By R.P. Jean Baptiste du Tertre. An illustration contained in this French text depicts the 1666 Battle of Sandy Point, apparently one of the major battles that took place that year during war between the English and French settlers. What is interesting about this illustration is that in the background of the fighting depicted a town is clearly shown. Therefore, the Sandy Point referred to in the illustration’s title was not just a beach but an already established settlement. Du Tertre’s depiction of the Battle of Sandy Point is the earliest reference uncovered thus far to the town of Sandy Point

By the nineteenth century Sandy Point had become an important slave trading port and a focal point for trade, in the form of both legal trade and smuggling, as well as communication between the British and Dutch West Indies. John Newton, the slave trader who later claimed a conversion to Christianity, records landing at Sandy Point on more than one occasion in his Diary of a Slave Trader.

Whereas in the French islands, such as Martinique and Guadeloupe, slave auctions typically took place aboard the slave ship, Newton recounts that in the Leeward Islands the auctions occurred ashore. While it is uncertain where exactly in Sandy Point slave auctions took place, whether at Pump Bay, Downing Street or some other location, local folklore among Sandy Pointers claims that an unoccupied lot of land known as The Pound was once a slave market. The Pound is located above the Methodist Cemetary on Downing Street. It has not been possible thus far to verify The Pound’s reputed past but what is interesting is that even some younger members of the community are familiar with The Pound’s alleged association with the nefarious Slave Trade.

The late eighteenth century was a time of heightened tensions in the Caribbean. A French invasion attempt on St. Kitts was expected, it was not a question of if but when. In 1779, a large detachment of British troops were deployed to St. Kitts. The soldiers were landed at Sandy Point and met by members of the Assembly. As the number of troops was too great for them to be adequately housed at the fortresses, accommodations were rented in Sandy Point and Dieppe Bay. By 1796 there were 150 soldiers and officers living in Sandy Point and Dieppe Bay. The majority of them may have been residing in Sandy Point for in 1802 it was recorded that there were 105 soldiers living there.

When the anticipated French attack came in 1782, Sandy Point found itself centre stage with the invading force occupying the town, consequently attracting heavy artillery fire from the defensive positions around Sandy Point. After a month long siege British forces on St. Kitts capitulated to the French but by 1783 the island was returned to the British under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. Within half a century slavery in the British Empire was legally ended and by the 1890s the last military garrisons were withdrawn from Sandy Point’s primary defences and other locations throughout the British West Indies. With India’s star on the rise and the British West Indies strategic value on the wane it was seen as no longer necessary to maintain expensive defences at small island ports such as Sandy Point.

However, while Sandy Point was no longer a strategic priority for British and French generals and admirals, the port town would up to the mid twentieth century come to play an increasingly important role in the lives of many people in the islands neighbouring St. Kitts. This we shall discuss in Part Two.