Ralph Cleghorn was a free coloured who was born in St. Kitts. Robert Cleghorn, his white father sent him to England at age five to acquire an education. Shortly after he returned to the island in 1823 at the age of 18, his father died at sea. Ralph returned to England to conclude some business arrangements and made his way back to St. Kitts two years later. He married Maria Berkeley, a free coloured woman on the 24th July 1824. Through the intervention of a friend who advanced him merchandise on the basis of his good name and on his expectations from his father’s will, they opened a dry goods store. At first the business produced an annual income of £1200 but as Cleghorn’s views on slavery became known his business declined. From his father, Ralph inherited cattle and other assets which together with his contacts in England stood him in good stead when setting up his business. In 1829 Cleghorn owned 13 slaves whose ages ranged from five months to twenty seven years. Eventually all were manumitted.

In 1828, Cleghorn was among sixteen men who signed a petition addressed to the Council requesting the reform of “laws and policies conceived in the spirit of the time, centuries ago” which upheld a system that was hurtful to them and prejudicial to the interests of the community at large. In the following year Cleghorn was delegated by his peers to present their petition to the Colonial Office. They were requesting that civil rights be extended to them as a class. This was a time when free coloureds were denied most rights enjoyed by the whites in spite of the fact that they contributed as much as the whites did to the society in which they lived. As an agent for the cause of the free coloureds he spent considerable time in Britain lobbying officials on behalf of his comrades and transmitting to the island important information and recommendations. Having spent most of his life in a more liberal English environment he felt resentment towards the restrictive nature of the society he found himself in. His sentiments towards the West Indian society were expressed in a letter to Zachary Macaulay:

I can most conscientiously declare that I never (and trust I never shall) imbibe any feeling, upon the subject of West Indian manners and policy than that of disgust and opposition, which is only strengthened and increased as I know more of them.

In 1829 Governor Maxwell again expressed concern regarding the disabling laws that still existed in the colony. Finally in an Act of 1830, Cleghorn and several other named men of colour were granted full enjoyment of their civil rights.

It was at about this time that Cleghorn became involved, at great risk to himself, in the Betto Douglas case. Betto was a slave on the Earl of Romney’s plantation who felt that she was being denied the freedom that had been promised to her. Cleghorn was one of the persons who assisted her financially during her period in hiding. Had his complicity been discovered he would have been liable to pay her owner twelve shillings a day for every day of her absence. His involvement was suspected but he and others assisting Douglas had suggested that she might have left St. Kitts.

Yet his efforts continued. Because of his strong anti-slavery views, Cleghorn made frequent visits not only to the Colonial Office but also to the Anti-slavery Society. Under his influence the cause of the free coloured became closely associated with the termination of slavery. They came to realise that as long as slavery existed they would continue to face discrimination and many free coloureds on St. Kitts openly campaigned for Emancipation.

In 1833 Cleghorn and John Berkeley, another free coloured were appointed an aides-de-camp to Governor MacGregor of the Leewards. Two of the white planters nominated to serve with them refused the appointment although they had previously agreed to accept. This was a reflection of the strained race relations that existed in St. Kitts. The Attorney General, Charles Thompson, who had recommended the appointment of the free coloureds was totally ostracized by the rest of white society on the island. The planter class protested “because one is a shopkeeper and the other a lawyer’s clerk and lately from behind the counter and not at all to be associated with.” However the Antigua Weekly Register saw through the class considerations and accused the planters on St. Kitts of wanting “to hold the reigns of office... to the end of time.” The paper went on to defend the men’s “respectability of character, their excellent education’ and pointed out that they had been accepted in “polished society” during their travels in England and on the Continent.

In his letter to Macaulay, Cleghorn described his very limited circle of friends on the island and lamented the difficulties he was experiencing in making a living for himself and his wife. In order to circumvent the boycott of his business he had placed its running in the hands of another person. Even this person was expressing concerns that through his association with Cleghorn he to would become a target of unpopularity. His letter mentioned vacancies for the posts of Provost Marshall and Stipendiary Magistrates and he expressed the hope that he would be considered as a candidate. He especially wanted to serve in a post “beneficial to a class of people whose interest I have espoused even to my own prejudice.” In 1834 Cleghorn travelled to England seeking the appointment of Provost-Marshal of St. Kitts.

Meanwhile the Emancipation Act came into force. Cleghorn’s view was that ‘immediate and unconditional freedom’ should be granted to the slave population. Since that was not likely to happen he accepted the Emancipation plan as the ‘best approximation yet proposed’. He warned however that

Slaves will not easily be brought to agree to any plan which shall preclude their unrestricted admission to entire emancipation, especially the emancipation of the will - enabling them to select their own employers.

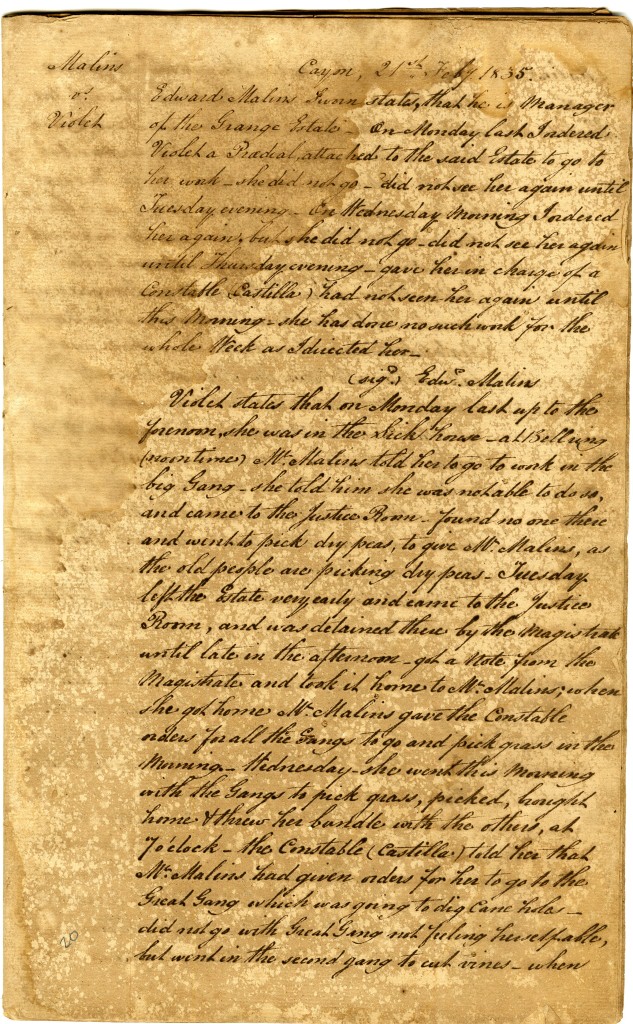

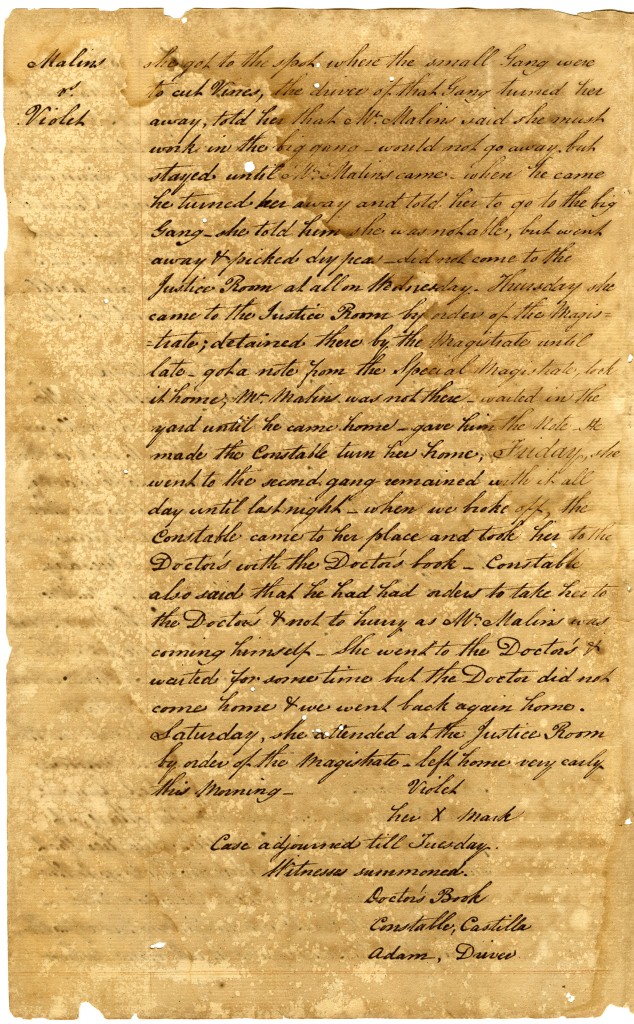

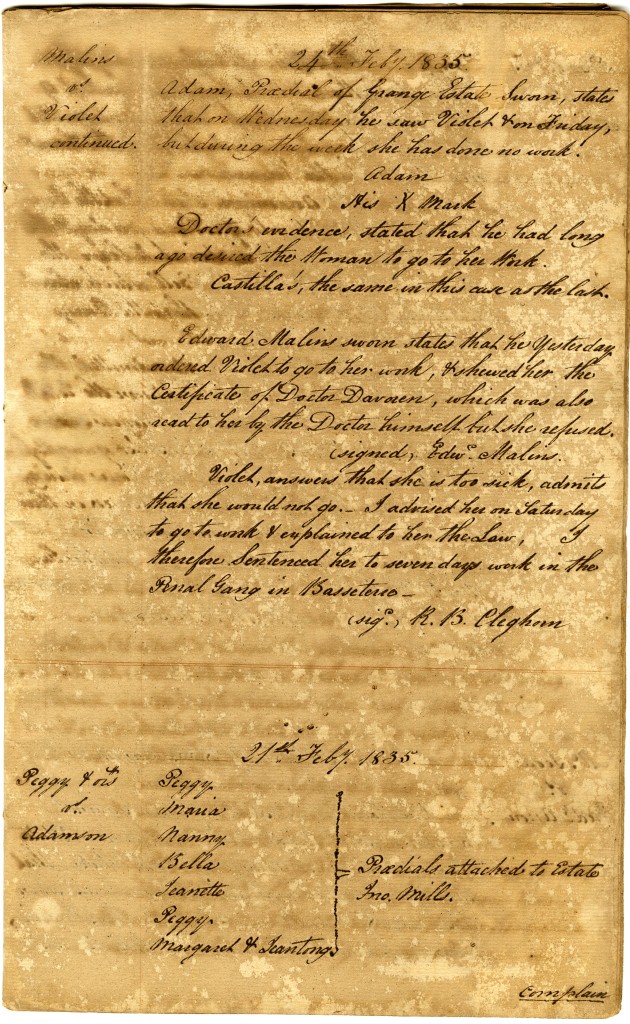

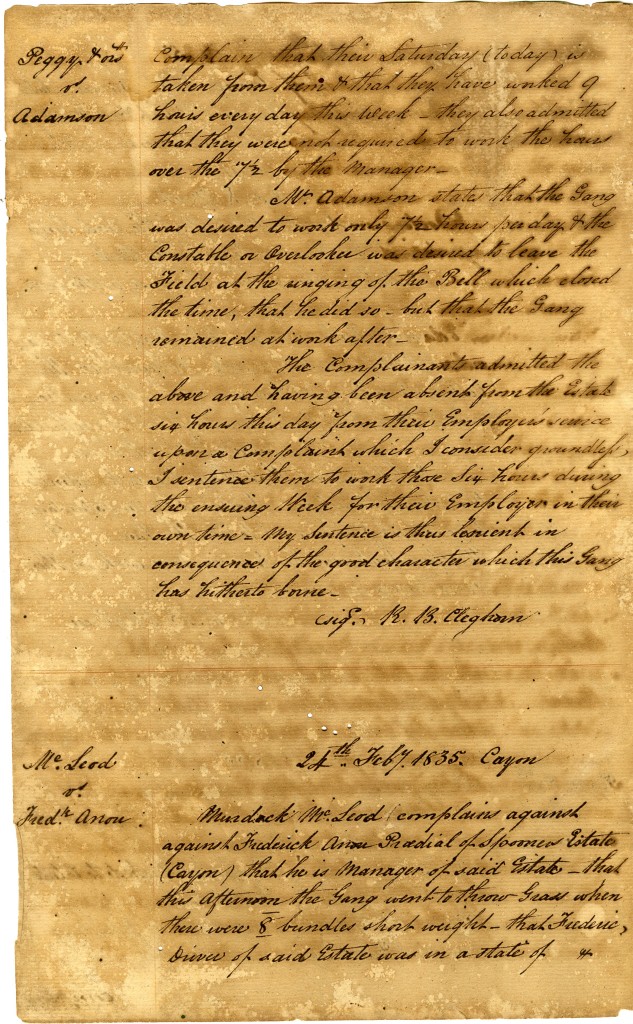

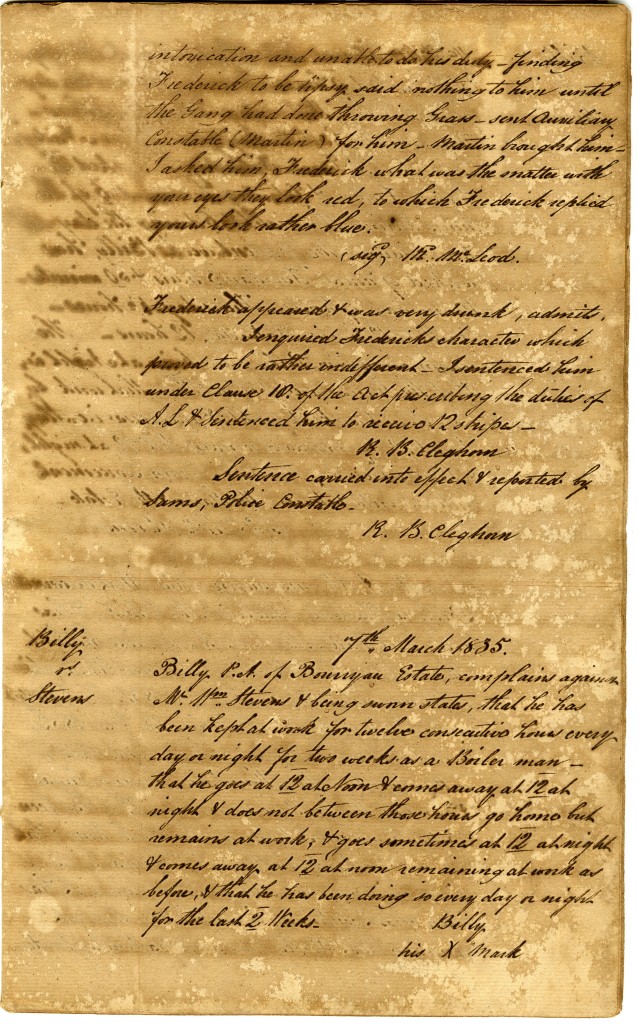

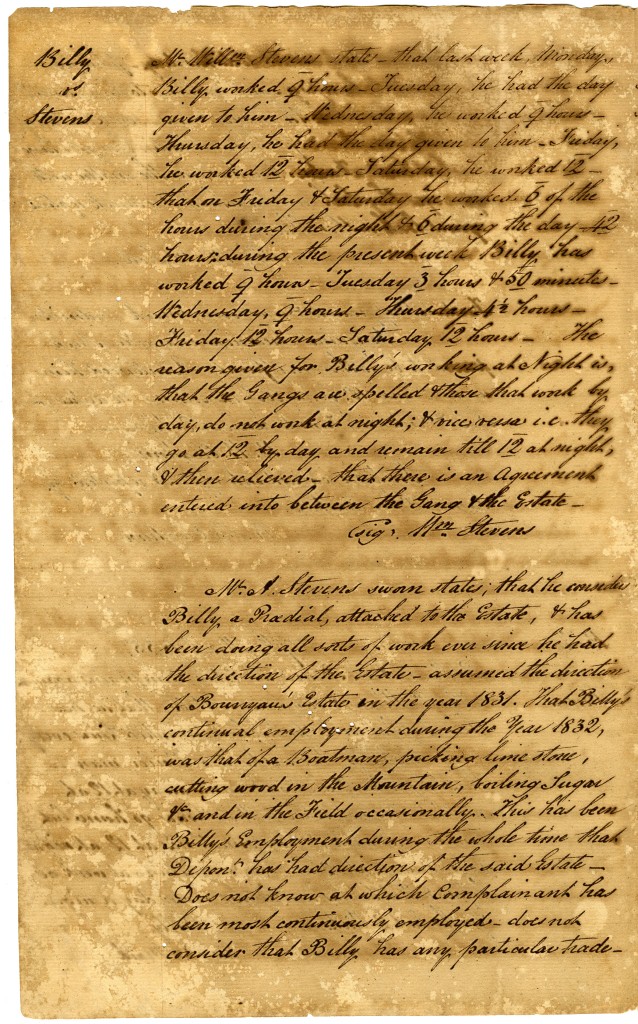

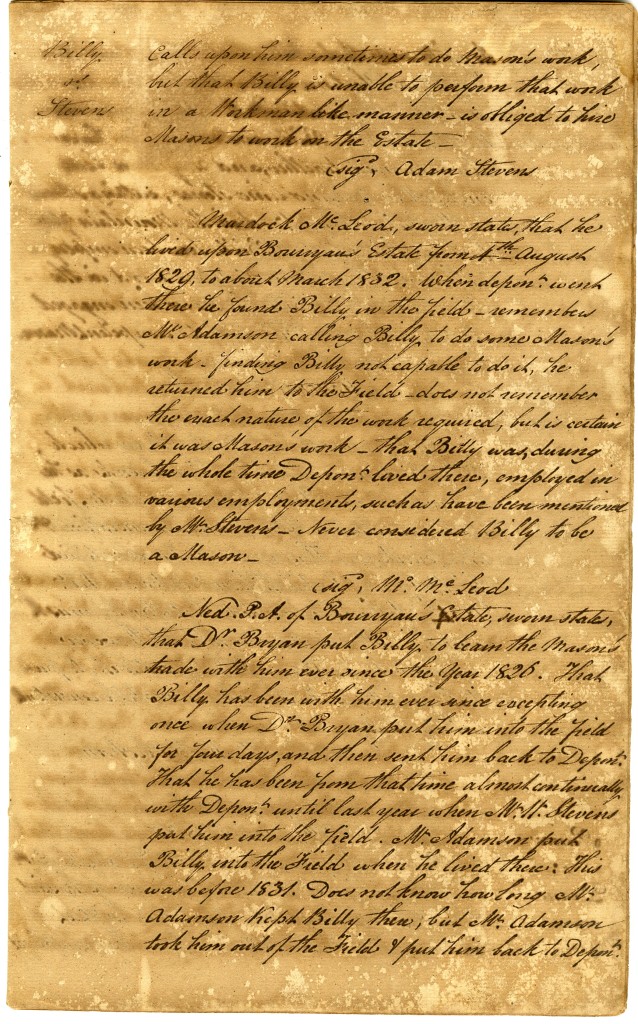

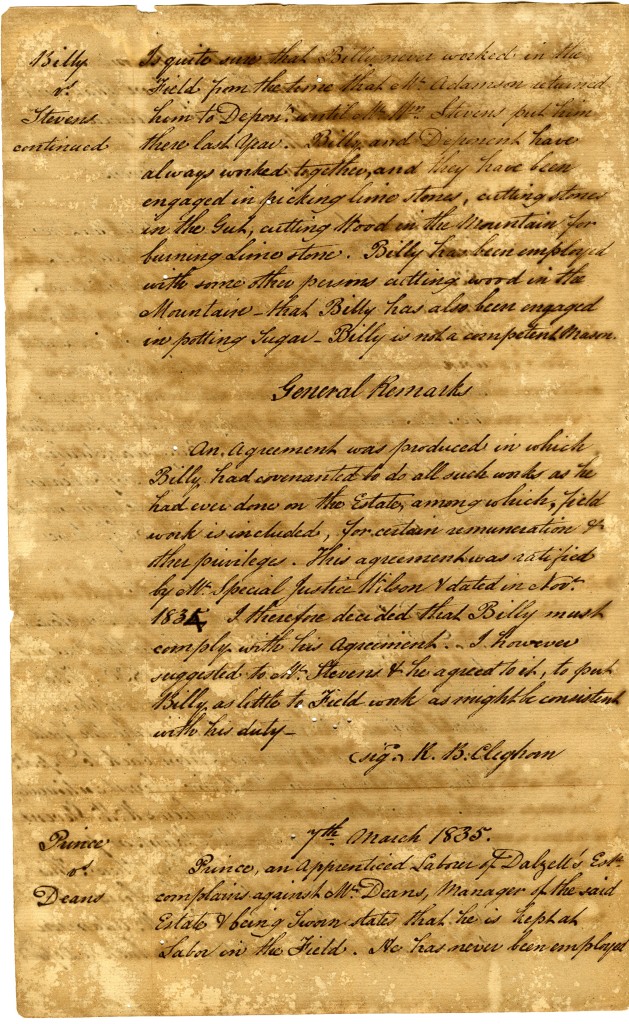

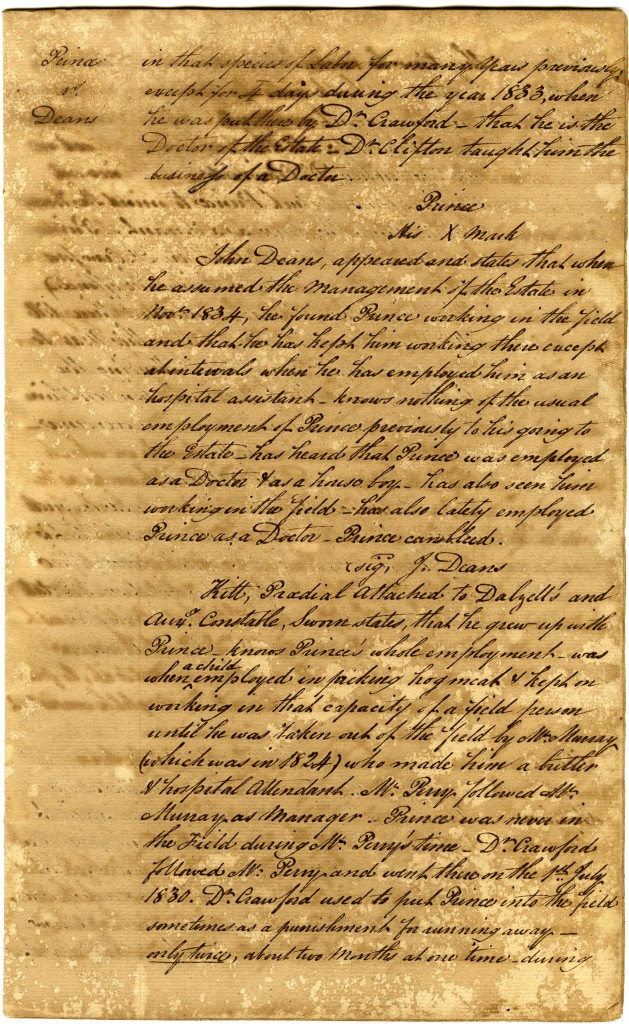

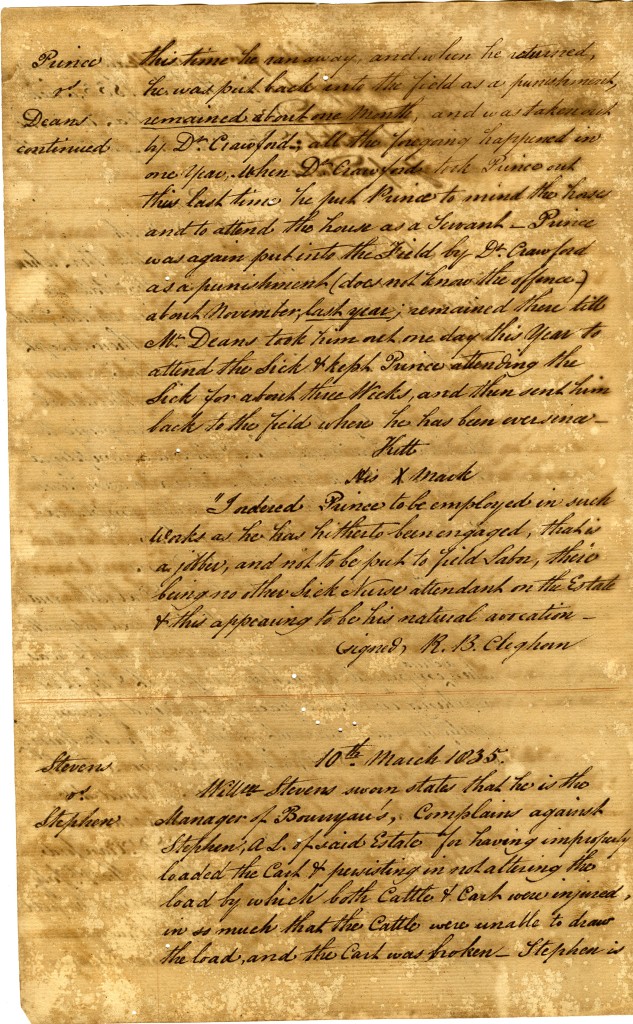

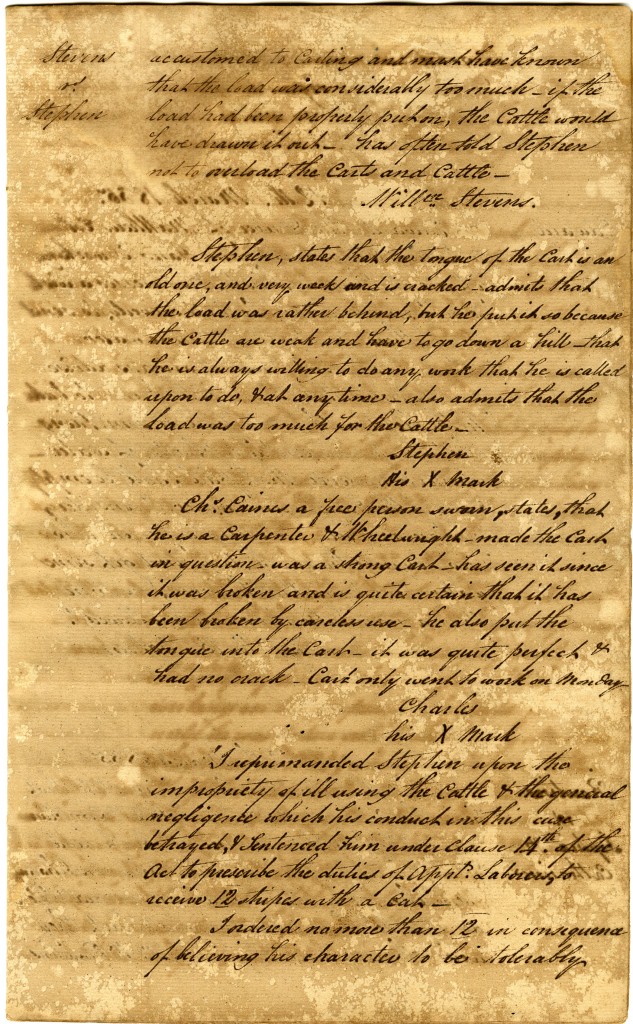

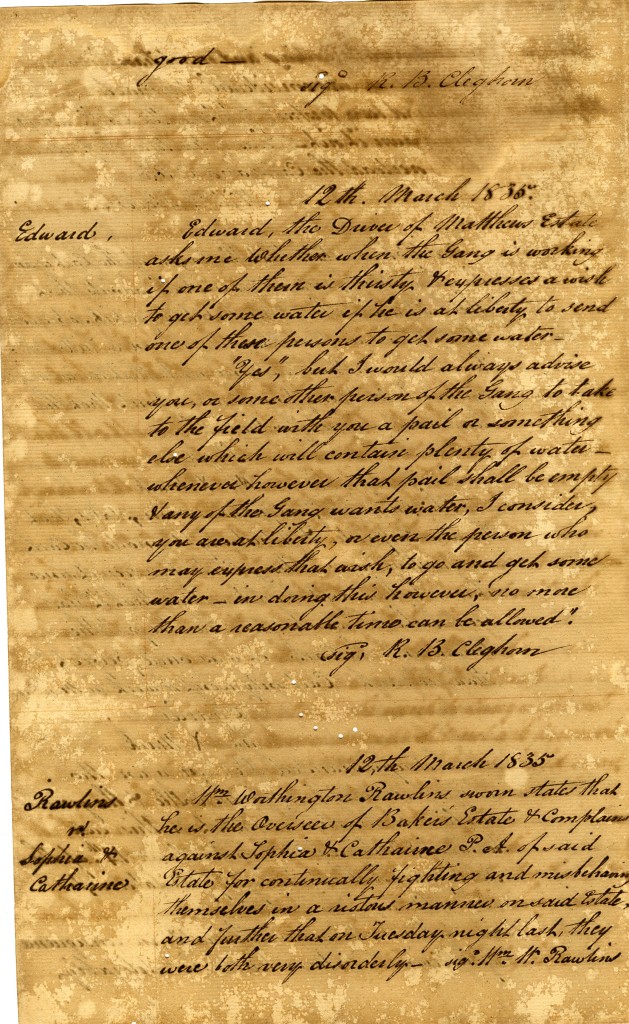

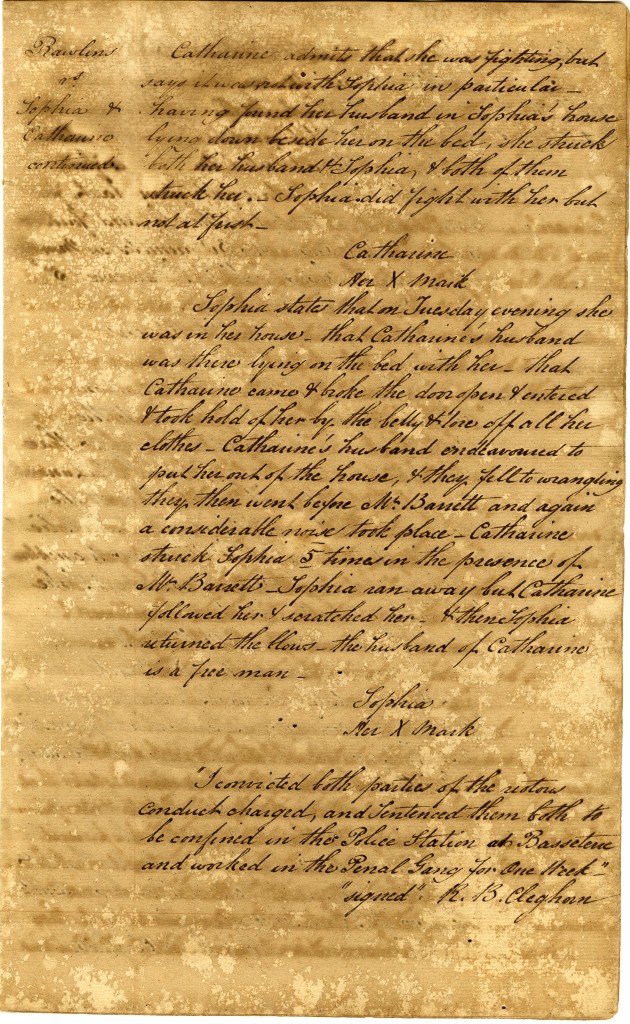

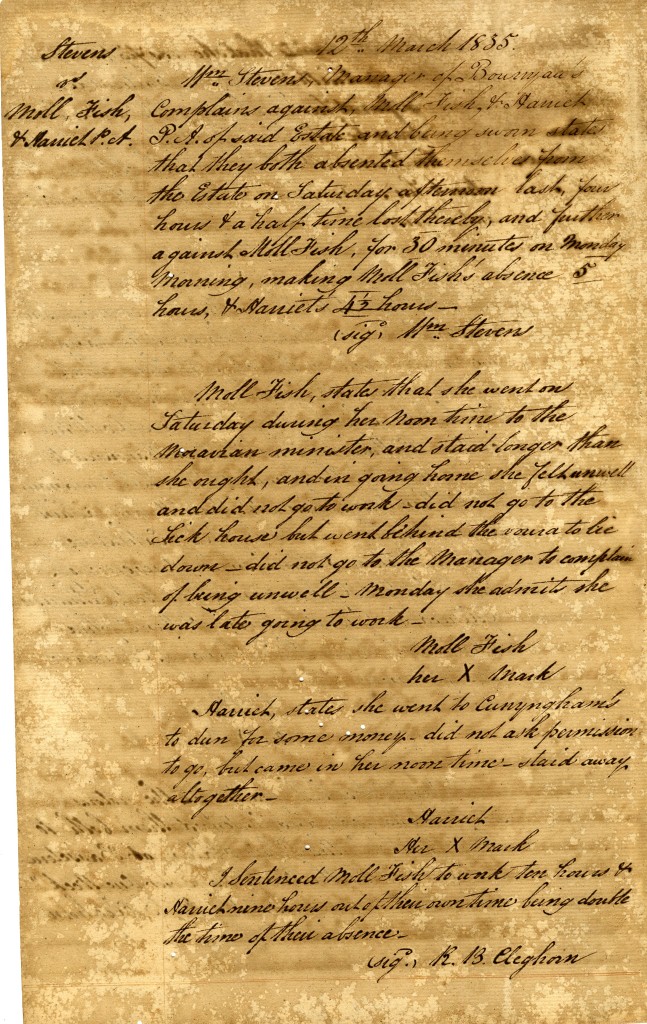

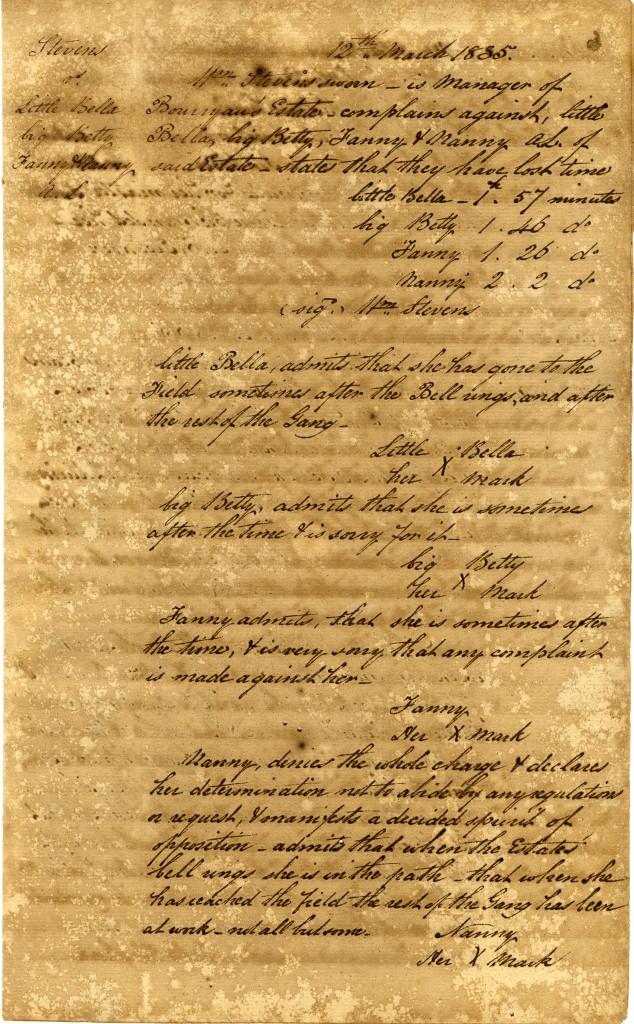

The slaves’ opposition to apprenticeship had the support of most of the free coloureds and of some of the white population. However, this was not enough to cause the abandonment of the idea. Slave discontent caused social unrest in St. Kitts in 1834. As a concession to the new apprentices, the Governor of the Leeward Islands appointed Ralph Cleghorn as Special Magistrate.

Ralph Cleghorn died on the 17th March 1842.