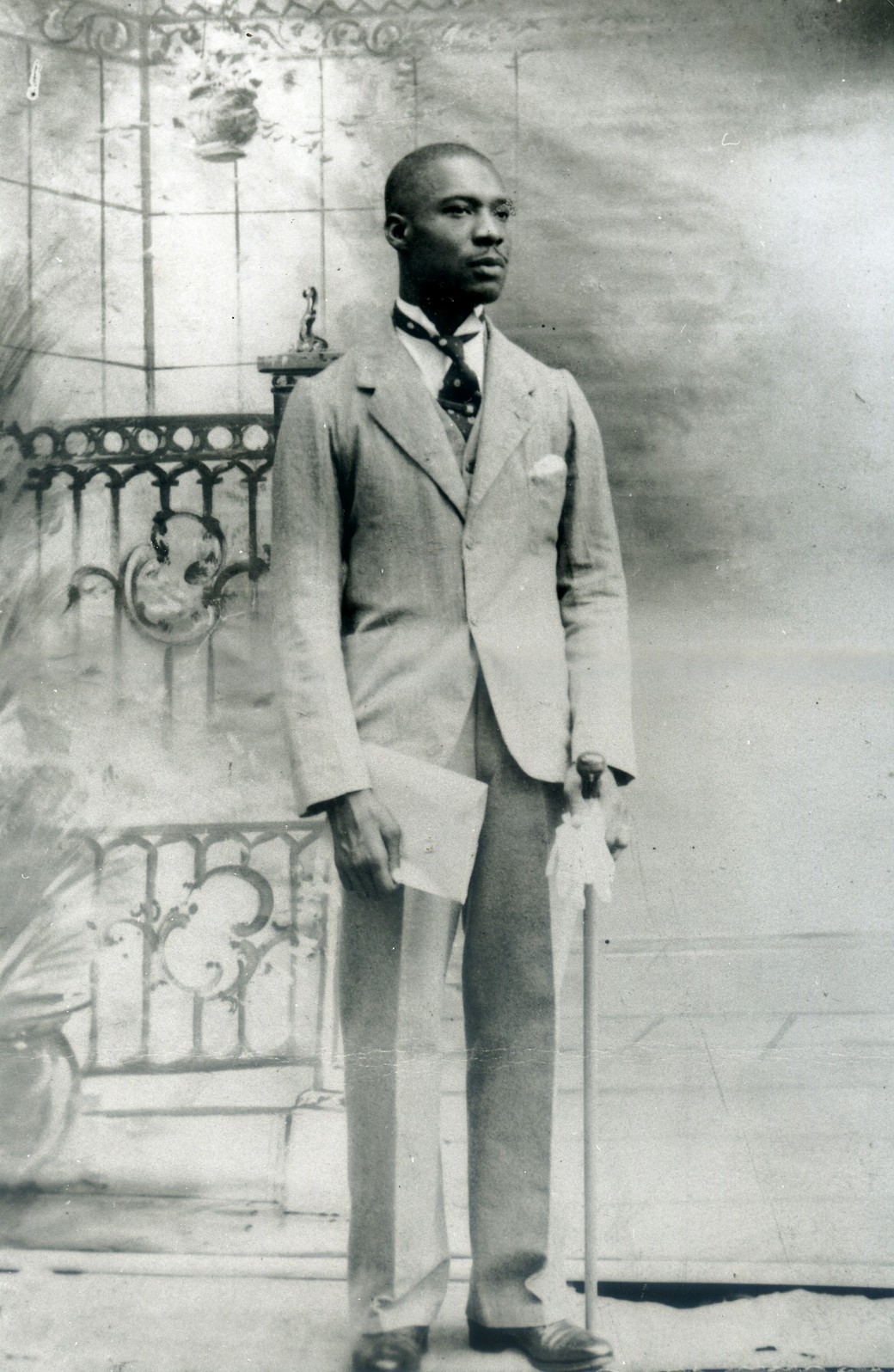

Robert Llewellyn Bradshaw was born on the 16th September 1916 in St. Paul’s Village, St. Kitts. His mother, Mary Jane Francis was a twenty-year-old domestic servant, his father William Bradshaw was a blacksmith who migrated to the US when his son was only nine months old. Young Robert, who was described by some as a dull and reticent youth, was brought up by his grandmother who ensured that he behaved himself and went to school. The family was far from being wealthy, there was no luxury but food was plentiful and fresh.

Robert’s grandmother was responsible for his discovery of something called the Union (the popular name of The St. Kitts Benevolent Association). Every morning before going to school, she took him with her to Belmont Estate where she worked to help her weed cane. On Mondays she would give him a penny or three penny bit as her Union dues. This, the boy had to give to Gabriel Douglas, the local Union representative who lived just at the entrance to the school.

By age 16, Robert had earned three Seven Standard Certificates, the highest education attainment in the primary schools of the period. He had even taught as a pupil teacher for a short while before he went to Basseterre where he became a machine apprentice at The St. Kitts (Basseterre) Sugar Factory, the most prestigious employer in the Presidency. His mother was then caretaker of the guest house at the Factory and young Robert moved in with her and got a glimpse of life at the managerial level. He could not help but compare the way of life of the white managers at the factory to that of the black workers in the village where he grew up. The disparity troubled him greatly. When one day he accidentally discovered a torn document showing the profits made by the factory he realised the extent of exploitation that was taking place.

In the machine shop, Adam Claxton, a welder, suggested that Bradshaw should join the Workers’ League. His membership was seconded by Harry Audain. However his career as a machinist did not have a chance to take off when in an accident in the machine shop Bradshaw injured his right hand and the doctors were unable to restore its full use. Bradshaw stayed in the tool room of the machine shop where he earned two shillings and three pence (54c) per day but he also turned his attention to more academic pursuits. His mother paid for a correspondence course with the Regent Institute in England and two boys from the St. Kitts-Nevis Grammar School who worked in the Factory Laboratory helped him with his studies. Later, Charles Halbert, the owner of a bookshop in Basseterre and a strong advocate of black pride and self-sufficiency became his friend and confidant and helped to inspire and mold his political ideas.

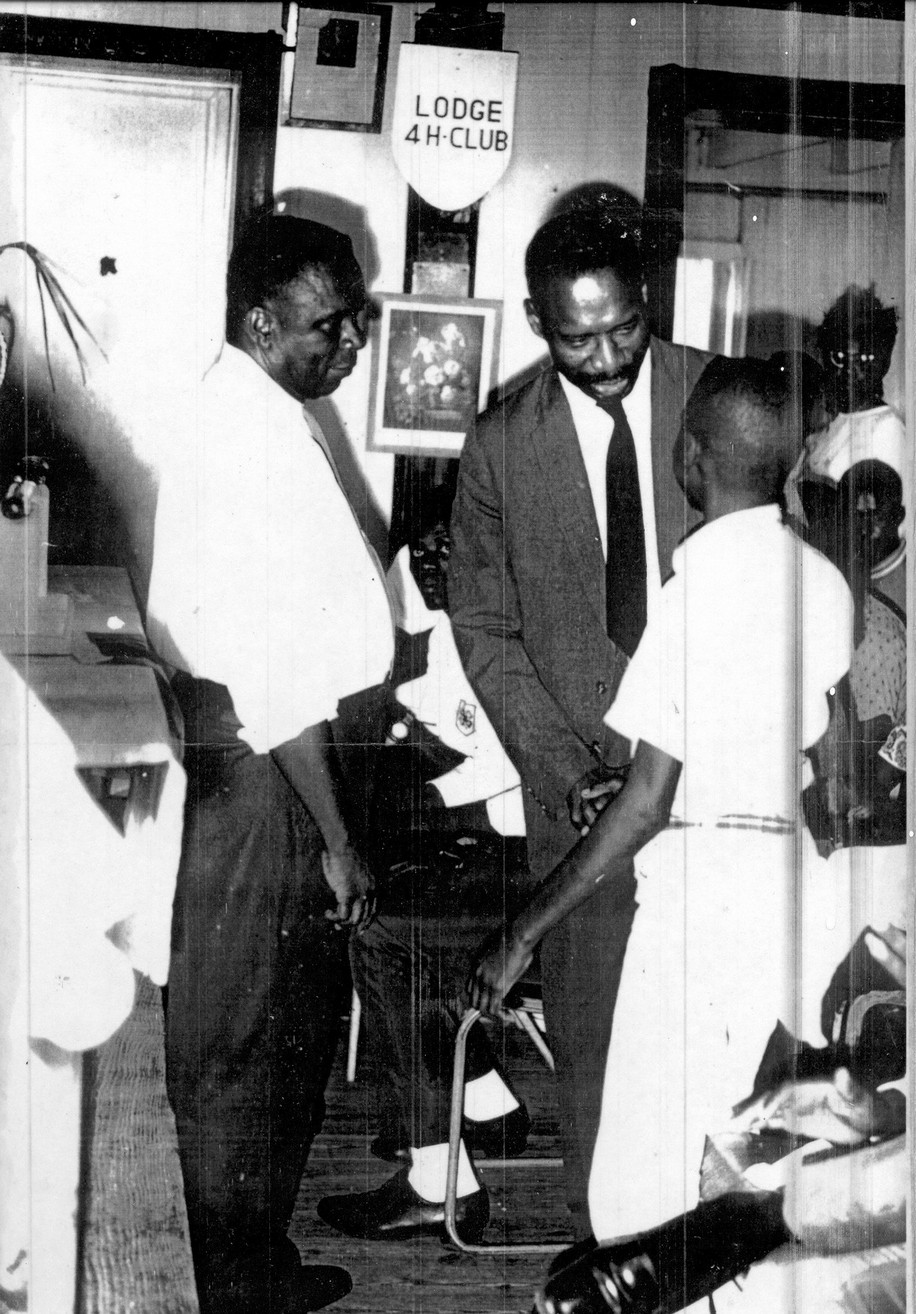

1940 marked a turning point in Bradshaw’s involvement in the union. A strike for higher wages cost him his job at the Factory and he was taken on at the newly formed St. Kitts Nevis Trades and Labour Union as a clerk. Bradshaw also became the first secretary of the Sugar Factory Section of the Union and a member of the Executive Committee. In 1944, following Sebastian’s death, Bradshaw became Union President and vice-president of the Workers’ League and four years later lead the Union through the throes of the Thirteen Week Strike. The scope of labour activity had broadened as it was recognised that wages were not the only problem facing the workers of St. Kitts and change had to involve every aspect of life if the situation was to improve. Among the achievements of the period was the fact that workers could no longer be arbitrarily charged for not reporting for work.

The 1948 strike sparked off the Soulbury Commission of Inquiry into the organization of the sugar industry and the Labour Leader was appointed to it. Throughout the hearings, Bradshaw noticed that the planters and factory management had the ears of the Commission but the workers were not given a fair hearing. Dissatisfied with the totality of the Commission’s conclusions, Bradshaw wrote a minority segment which was included in the report. He even went to England in an effort to bring this bias to the attention of the Colonial Office. The prolonged nature of the strike drove the more conservative middle class into an alliance with the planter class. This took the shape of the Democratic Party launched by the end of that year.

Bradshaw’s activities were not limited to the local scene. In 1945 he took part in the establishment of the Caribbean Congress of Labour and was elected its first assistant secretary. In 1947 he represented St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla at the “Closer Union” Conference for the amalgamation of the Windward and Leeward Islands and at the Montego Bay Conference which discussed the Federation of the West Indies. Two years later he participated in the establishment of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions in Brussels and was elected to its first Executive Committee.

This was the period when in control of the Union’s activities, Bradshaw thought it offensive that a racist South Africa would be permitted to export its products unhindered to St. Kitts and Nevis. As a result he spearheaded a boycott of produce from the Union of South Africa. Especially hard hit was the wines then the principal product imported. This bold move, was followed by action in the Legislative Council which effectively barred the recruitment for service of prospective employees hailing from South Africa.

Operation Blackburne found Bradshaw on the streets of Basseterre leading a huge demonstration. It was an effort on the part of the Labour Movement to draw attention to its claim that the Colonial Office should consult the representatives of the people before the appointment of Governors and Administrators for the Caribbean colonies.

In the political arena, Bradshaw was elected along with J.N. France and M. Davis to the island’s Legislative Council in 1946 and later became a member of the Leeward Islands General Legislative Council. He was again elected in 1952 when universal suffrage was introduced. Four years later when a ministerial system came into effect, Bradshaw was appointed Minister of Trade and Production after having seen service in the precursor training period known as the membership system. It was during this period that a rift developed between himself and Maurice Davis and R.J. Gordon of Nevis. It represented a much deeper growing hostility between the Labour movement on one hand and the middle class and the people of Nevis on the other.

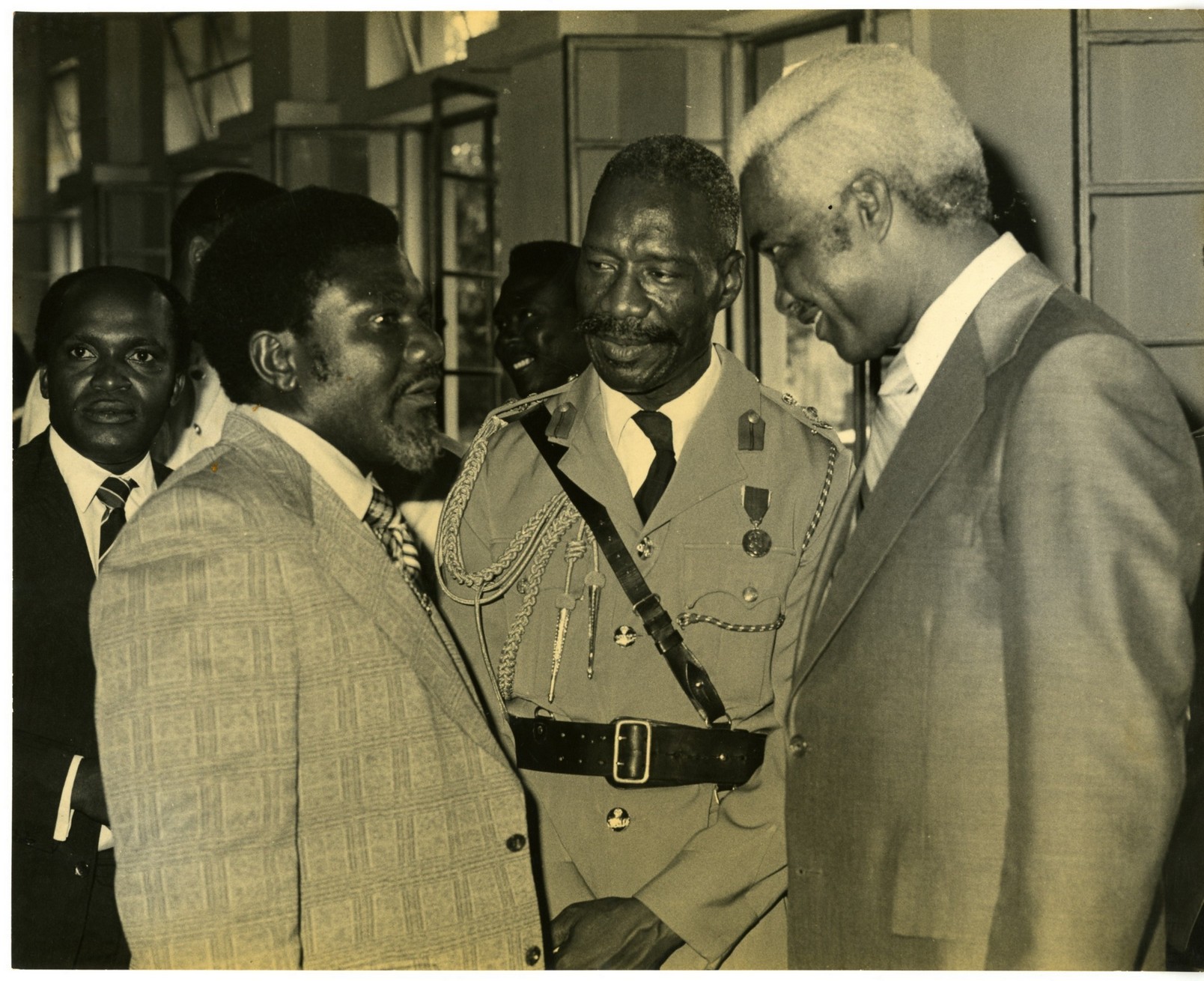

In 1958 Bradshaw was elected to the Federal Parliament and held the position of Minister of Finance. When the Federation was dissolved in 1962, Bradshaw felt that “we were ruining the one great opportunity we had of making ourselves a recognizable grouping on a national scale in the world.... the populations had given their leaders a mandate to form a Federation and bring it to Nationhood. The fact that we did not do so meant that we failed the people.” It was with a sense of weariness that he greeted the next attempt at regional integration as it took shape in the form of CARIFTA and later CARICOM. His commitment to the concept had not faltered but a sense of skepticism over how far it would go this time invaded some of his public speeches.

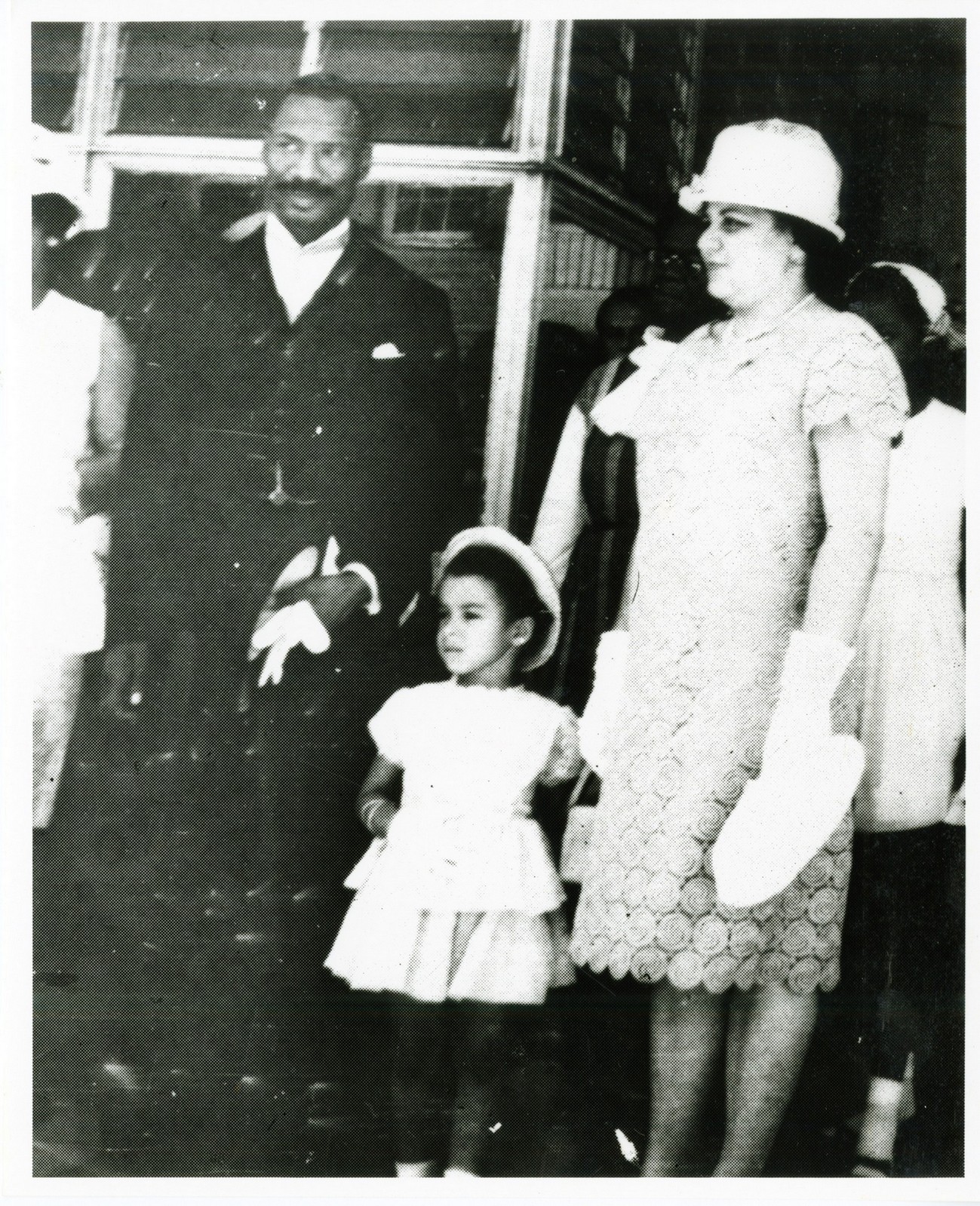

After the dissolution of the West Indies Federation, Bradshaw returned to St. Kitts and re-occupied a place in the local legislature. Milton Pentonville Allen, a local stalwart, who was later elevated to the status of Governor of the State, relinquished his seat in the Legislature allowing the returning Bradshaw to win the by-election by a landslide. After the elections of 1966, Robert Bradshaw was sworn in as Chief Minister and on the 27th February 1967 he became the first Premier of the Associated State of St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla.

The granting of Statehood opened the door to secession. Bradshaw had never quite reconciled the economic differences in systems of production of the three islands. St. Kitts was the only one of the three that had a largely landless labour force dependent on sugar earnings. It became the power base of the Labour Movement. However Nevisians and Anguillans were mostly self-employed giving rise to a totally different point of view in economic, social and political development. Those that made the move to St. Kitts often found that the policies advocated by the Labour Movement worked to their benefit but the ones that stayed behind did not share the experience.

Anguilla opted for secession immediately and with the active encouragement of the People’s Action Movement and the procurement of financing from interested foreigners, agitation progressed leading inevitably to British Government intervention. Bradshaw, who had watched with anguish only a few years previously the disintegration of the West Indies Federation was being called upon to dismember his own tiny state into its separate components. He refused to allow secession on the grounds that the constitution stipulated that any such move must be initiated by the Legislature of the Associated State. He felt compelled to stop such disintegration and perhaps driven by this obsession his methods lacked a sound legal foundation. Such was the case on the issue of detention of suspects, a matter that brought him in conflict with the Governor, himself a constitutional lawyer. Sir Fred Phillip advised that charges be brought immediately and that these be as specific as possible so that a detainee could rebut them without difficulty to avoid challenges in court. However in this instance emotions were running strong and Bradshaw chose to ignore the advice of the Governor and lost the case.

In the end, the metropolitan government achieved secession for Anguilla by the enactment of an Order-in-Council. Nevis lingered on, threatening to secede at any time but the Premier remained committed to a unitary state and a West Indian Federation. This however did not distract Bradshaw from seeking Independence.

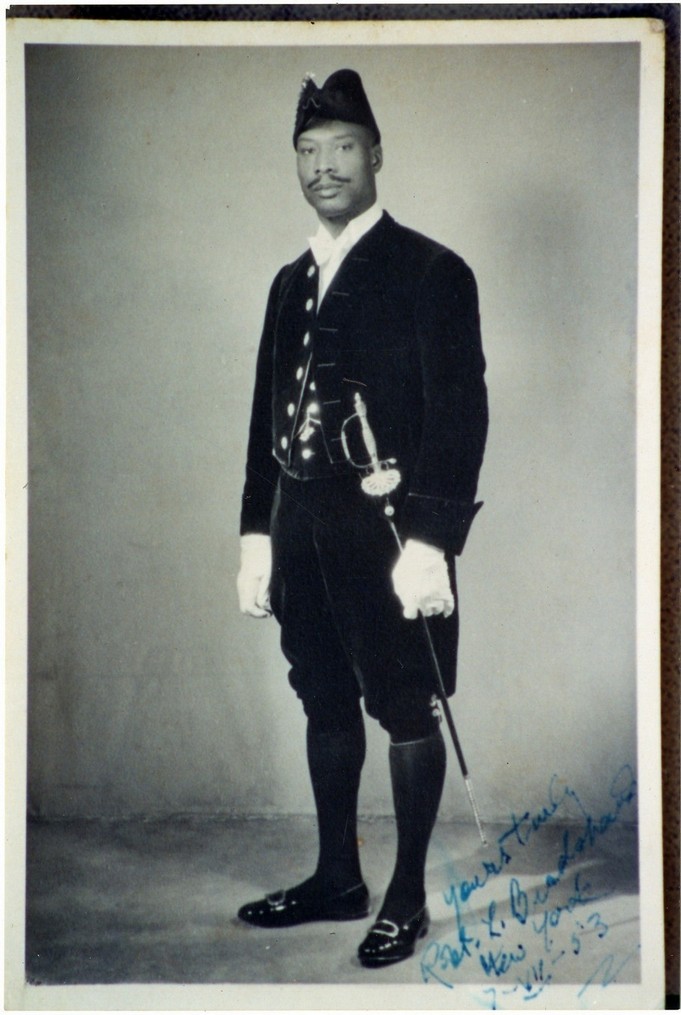

Outside of politics, Bradshaw had a flare for fine living. This was demonstrated in his an interest in antiques which he avidly collected on his trips abroad often to the consternation of those who accompanied him and knew nothing of the value of the items he purchased in markets of England and elsewhere. He also had a taste for good cigars and fine wines. On a more aristocratic level he showed a great deal on interest in Heraldry. When the Coat of Arms for the new Associated State was required he critically and authoritatively examined all submissions then presented the Executive council with a design that was considered “original and appropriate.”

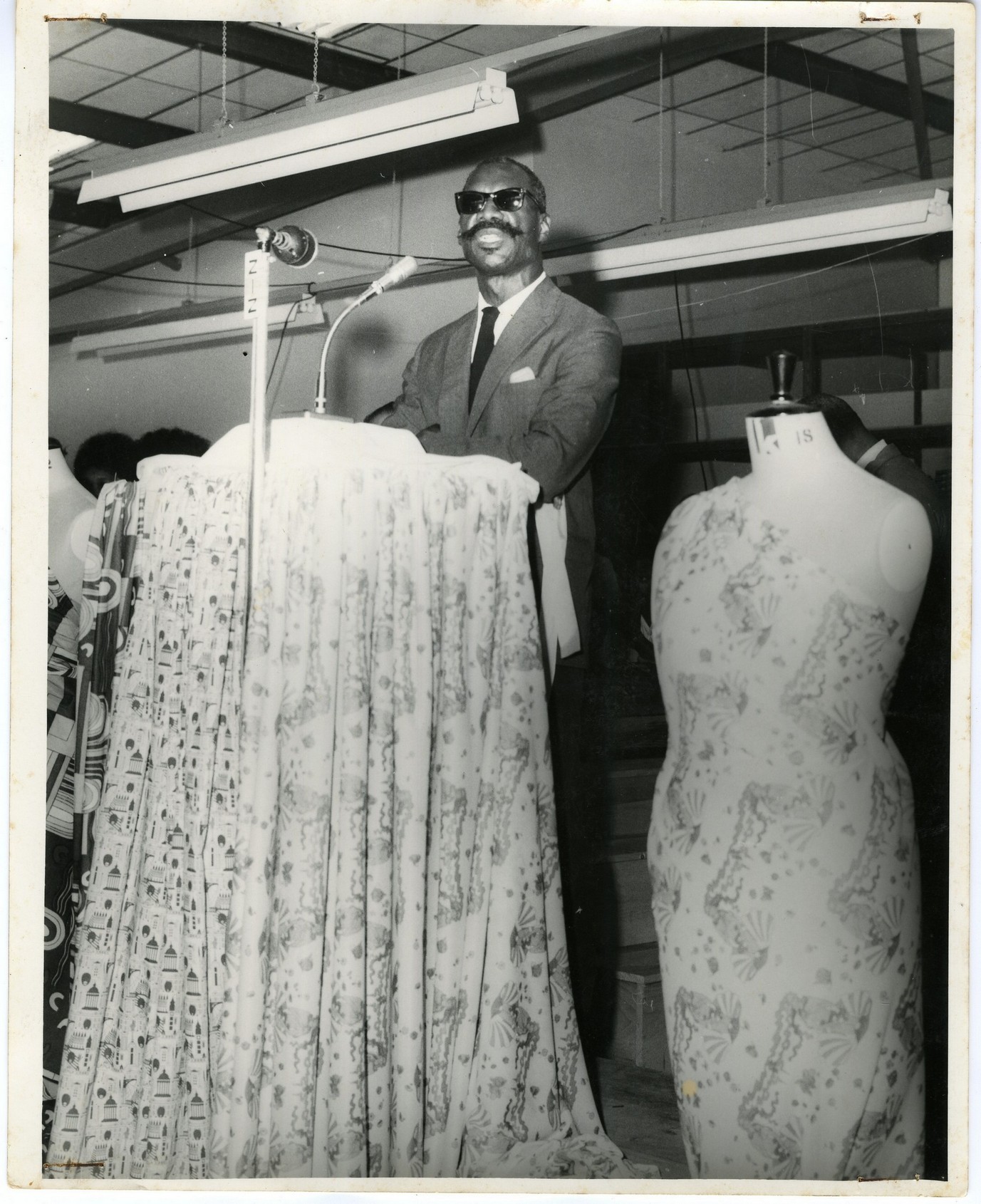

Throughout his career, Bradshaw maintained a great interest in the Sugar industry in St. Kitts. Its survival and the welfare of the workers that depended on it were of great concern to him both as a political and as a trade union leader. With the acceptance of Ministerial powers came the responsibility for a viable economy. In the mid-1960s came a decline in sugar production and international sugar prices. Bradshaw embarked on a two-pronged solution - the rescue of the industry and diversification of the economy. Sugar could not be abandoned as seventy per cent of government’s revenue was generated by it and the employment of many Kittitians who were the basis of the political strength of the Labour Movement was dependent on it. However rescue operations were being thwarted by the indiscriminate sale of sugar lands and the inability of the planters to effectively put in place the measures required for the survival of the industry. So in 1975 Bradshaw took the bold step of acquiring the sugar lands and then the sugar factory. To many planters the move came as a relief but then within a very short space of time their monetary expectation in the way of payment multiplied to a sum far in excess of what Bradshaw was prepared to offer. Whilst the land stayed under cane, the matter of payment became the subject of a legal battle that was not resolved till much later.

In 1975 the Labour Party had two main issues to put before the electorate: “that the sugar lands should irrevocably remain the property of the State and that rapid progress towards independent status within the Commonwealth” be sought. All the while following Statehood, Bradshaw and his administration set about putting in place the machinery that would give the future micro-state a chance to survive. Dramatic changes took place in education, tourism, Social security, and the infrastructure.

By the time Independence talks commenced in earnest in 1977, the foundation of the new state had been placed on sound footings. But by then, the Premier was a very sick man. He underwent major surgery in St. Kitts in 1976 and had to undergo another major operation in London in January 1978. He died on the 23rd May of that year surrounded by family and friends at his home in Fortlands, Basseterre.

Commenting on his legacy, The London Times said, “he has left behind him in St. Kitts a solid structure of social services and amenities considering the slight resources of his State.” Sir Fred Phillip who had to deal with him during the Anguilla crisis said, “For all his faults,, he was a man of high principles and had the courage of his own convictions.” Robert Bradshaw stood out as a forceful leader, a skillful politician and an important catalyst for real changes in St. Kitts and in the broader Caribbean. On the 16th September 1998, he was posthumously given the title of Knight Commander of the Order of The National Hero.