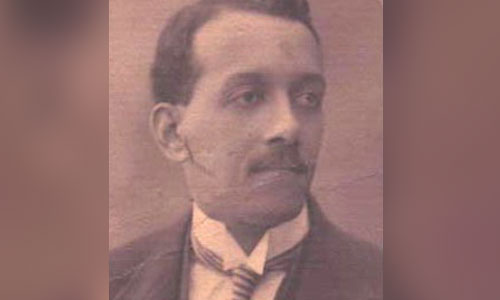

Clement Malone was born in 1883 in Antigua into a coloured family whose members had risen to prominence as merchants, clergymen, lawyers and schoolmasters. He was educated at the Antigua Grammar School and after leaving school was employed as a teacher for one term. It was a position that young Clement did not regret leaving. He entered the civil service of the Leeward Islands and, for a number of years, was assigned to St. Kitts as a clerk in the Treasury Department.

After obtaining study leave, he proceeded to London and enrolled as a law student. He was called to the bar at Middle Temple in 1916 during the early stages of World War I. On returning to Antigua, he was called to the bar of the Leeward Islands and then settled to practice his profession in St. Kitts. The following year he married Ethel Malone and together they had three sons.

The charming “ Mr Clem” as he was affectionately known by the people of St. Kitts and Nevis, quickly gained the trust, respect and affection of the community. His thorough knowledge of the law, his tenacity in maintaining his point of view and his courtesy won him the admiration of Bench and Bar alike and earned him considerable patronage. Within a short time his law practice extended to Antigua, Montserrat and at times Dominica. He even had the unusual experience of representing a man in St. Maarten in a Dutch court. His clients ranged from ordinary men and women to the powerful Barclays Bank and Royal Bank of Canada. When, in 1921 Malone applied for an appointment in the civil service, Administrator Burdon’s reported that he bears a high character in the community and is suitable for employment in any legal post for which colour is not a bar.

On the 28th December 1918, Malone and a small group of coloured middle class professional and business men formed the St. Kitts Representative Government Association (RGA) with a mission ‘to secure the achievement of popular representative government’’. By the following year, 330 men had become members of the RGA and Clement Malone was its President. In a Petition addressed to His Majesty, the RGA requested a franchise that was exclusively adult male who either owned real property valued at £50 or over, or paid an annual rent of £10, or made a yearly salary of £50 or an income of £30. Acting Administrator Wrigley described the Association as a creation of Clement Malone whom he accused of seeking public attention and dismissed it as lacking in support from among the influential persons of the Presidency.

The RGAs efforts produced no tangible results and it quickly disappeared from the scene but it was replaced in 1922 by the Taxpayers’ Association. Its target was the introduction of Income Tax and as based on the premise that persons who paid taxes should have a say in government and so it made issue of all the shortcomings of the colonial administration. Once again Malone was an active member. To counteract the opposition, Burdon recommended that Clement Malone be appointed to the Council but he saw no reason for equality of representation between the planters and the other social classes. In 1925, Administrator St. Johnston recommended that Malone be offered a place on the Executive Council on the grounds that he found the lawyer to be moderate in his views when he fully appreciated the real necessity for a proposal made by Government. However when the offer came Clement Malone declined to accept as he had publicly expressed the view that a member of the Legislative Council should not hold a position on the Executive of the Presidency of St. Kitts and Nevis. Later he changed his mind and accepted to serve on the Executive of the Colony which met in Antigua.

In 1935, Malone found himself caught up in the events that came to be known as the Buckley Riots. Along with Thomas Manchester, Victor John and William Seaton he did his best to defuse the tension caused by the heightened expectations of sugar workers. Their sympathetic, common sense approach persuaded a significant number to return to their homes but was not enough to put an end to the agitation of the remaining crowd. When in March, and April a number of persons were brought to trial charged with causing riots and other related offenses, Malone was there to take the case. He scathingly pointed out discrepancies in the evidence delivered by members of the police force whom he accused of collaborating to bring about guilty verdicts. His defence was described as aggressive, and successful. It certainly persuaded a jury consisting of middle class businessmen to acquit the accused. The following year the planters of St. Kitts and Nevis came in conflict with the St. Kitts (Basseterre) Sugar Factory over the price to be paid for canes supplied to the Factory. Clement Malone and J. R. Yearwood were sent to London to represent the planters’ interests. The negotiation produced an increase in the price of cane.

The 1937 election was contested by the Workers’ League and individual members of the Agricultural and Commercial Society. Clement Malone ran as an independent candidate and often appeared on the platform with W.E.L. Walwyn and P. Ryan but was endorsed by both organisations. As a result he won the largest number of votes from the small electorate. In politics, Malone proved himself to be a popular politician. Although at times an outspoken critic of Government, his sane judgement, and fearlessness won him the sometimes uncertain respect of the Administration and the esteem of the people.

On the 24th April 1940, Malone was appointed Puisine Judge to the newly constituted Supreme Court of the Leeward and Windward islands. This meant that he could not contest the elections of September that same year. His appointment was greeted with a sense of satisfaction among the people of the colony who saw it as a just reward for years of professionalism.

Clement Malone also served on various boards and committees. He was a moving spirit on the Education Board and Vice-President of the Cricket and Football Associations. In 1943 he was appointed to a Board of Inquiry into the trade dispute between the Sugar Producers Association and the St. Kitts Nevis Trade and Labour Union. The recommendations said that the Bonus to sugar workers should continue, that it should be paid in December and that it should be calculated solely on a percentage of the wages earned during the year. Estate pay books were to be made available to the Federal Labour Officer or an officer of the Trade Union in case of dissatisfaction on the part of a worker.

In 1942 Clement Malone succeeded Sir Wilfred Wigley as Chief Justice of the Leeward and Windward Islands. For the third time a coloured West Indian was being appointed to the highest judicial post in a colony. (Previous appointments were Conrad Reeves, Chief Justice of Barbados and Charles Lewis, Chief Justice of Sierra Leone.} This appointment meant that the new Chief Justice and his family would have to take up residence in Grenada. Two years later His Lordship received a knighthood in recognition for his commitment to the law and his contribution to society.

In Grenada, Malone soon found himself involved once again in social issues. 1947 saw the launching of the Grenada Cooperative Nutmeg Association. Whose objectives were to secure more stable price, to end the competition between Grenadian exporters, to eliminate the middleman and increase profits and to set standards of quality. Malone was foremost among those who spoke in support of the association and on that occasion his views were aired on radio in a speech entitled “A West Indian University.”

In 1951, it was his birthplace that needed his calm approach to volatile issues. That year Antigua found itself in the throes of a general Strike. The planters stopped the crop, claiming that it was a waste of resources to reap a crop of less than seven thousand tons a week. Other matters added fuel to the flames and in April the sugar curers at the factory refused to clean the mixers. Furthermore the AT&LU had not informed the employers that May 1st was to be celebrated as Labour Day and workers were to be called off the job. After May Day workers from all walks of life refused to return to their jobs and the AT&LU demanded the reinstatement of the sugar curers. Sir Clement Malone, who had retired from the Bench the previous year was called upon to head a Commission of Inquiry into the matter. and the adversaries were given the opportunity to air their differences. The proceedings started on the 11th June but were disrupted when a state of emergency was declared. British Troops had been called in and the AT&LU refused to appear before the Commission. The hearings ended on the 2nd August and in its report the Malone Commission accused the AT&LU of striking first and thinking later. The report sharply criticized the AT&LU but saw no reason for banning strikes. It also recommended the nationalization of the sugar industry in Antigua.

The 1950s saw the creation of a Federation of the West Indies. Sir Clements’s statements demonstrated a more down to earth approach to the initiative. he felt that practicalities should come before politics and suggested that the coordination of transport and communications services and a better marketing of the economic resources of the region should be the first steps towards creating a meaningful political unit in the West Indies.

Sir Clement Malone died in Trinidad on the 9th April 1967 at the home of his eldest son. He was 84 years old and still enjoying the respect and adulation of many West Indians.