Kathleen Manchester

Kathleen Dorothy, the only daughter of Thomas Manchester and his wife Ada Killikelly was born in Sandy Point on the 4th December 1923. Kathleen’s memory of those years are idyllic, picnics with her parents, hiding in the garden. They were marred by the memories of the Hurricane of 1928 which tore the roof of the family house. That same year Ada died and the little girl passed into the hands of four aunts. With no children of their own, Louisa, Gwendolyn, Winifred and Alice Manchester lavished their attention on their orphaned niece and treated her like a little princess. This left her father free to throw his energies into the political arena where he founded and, for a number of years, lead the Workers’ League.

At age five little Kathleen was sent to a school run by Miss Liz Clarke at Rose Cottage, Downing Street Sandy Point. Plagued with Tonsillitis throughout her early childhood, the little girl often had to spend days in bed with feverish colds. She read widely to while away the time amplifying both her vocabulary and her imagination. At nine years of age she entered the Girls’ High School or Miss Pickard’s school as it was then known where the girls learnt not only academic subjects but also practical ones such as first aid, home nursing and book repair. They were also taught to value dignity, discipline, cleanliness, service to and participation in the community. Her recollections of her school days were vivacious. Travelling to and from Sandy Point on a daily basis was no easy task in those days so arrangements were made for young Kathleen to remain in Basseterre during the week. She stayed at home of Mrs. Lou Challenger, her father’s cousin and the mother of his comrade-in-arms, Edgar Challenger.

In December 1941, Kathleen Manchester joined the Civil Service as a junior clerk in Administration. Her father’s failing business interests which had repercussions on her aunts’ fortunes and his declining health would have meant that she had to place herself in a position that would guarantee some independence. Thomas Manchester died on the 31st January 1943 and Kathleen continued in the service for another four years.

In 1949, , she went to Canada to pursue her studies. Alan Manchester, her paternal uncle gave her accommodation. Kathleen had hoped to pursue studies at the University of Toronto but a late arrival prevented her enrolment as a full-time student. Instead she opted to take evening classes at the same University. She left Canada in the spring of 1950 after having been involved in an auto-mobile accident.

On the 4th July 1958, Kathleen Manchester graduated with a Masters in English from the University of Edinburgh. She was probably the first Kittitian woman to achieve that academic distinction. She was also given an award by the Senate of the University to research Constitutional Developments in the West Indies since 1832 with special reference to the Leeward Islands for her Doctorate

Manchester visited St. Kitts soon after graduation on what she intended would be a research visit and in December she wrote a progress report on her work which showed that she had covered a great deal of ground in St. Kitts. However she now faced domestic obligations which conflicted with her academic commitments, as her three elderly aunts were ailing and in need of her support. Her plans for an early return to Scotland were put on hold but she continued the research for her doctoral dissertation.

To supplement her award from the University she also took a part-time secretarial post and worked as a lecturer for the Extra-Mural Department of the University College of the West Indies. She also taught English and History at her old school - the Girl’s High School. Her students remember her as an eccentric teacher who inspired them with her love of language.

Her interest in history seems to have coincided with a similar interest shared by Robert Bradshaw He was anxious to assist the daughter of the founder of the party he was leading. His recommendation that she should be given the job to manage the archives facilitated the research that Manchester wanted to do and he hoped that it would bring order to the records. Manchester threw herself into the job with a passion. She recognised the value of the records and hand copied records herself and at times paid some youngster to help her.

Her work however came to an abrupt end when someone raised a suspicion that her interest in the records went beyond research. Police were sent to her house to take possession of records that she had carried there and she was banned from returning to the Archives. It was a restriction that was repeated again in 1966 when she asked for permission to return to resume research for her Ph.D. and to double check material for her upcoming publication. Unfortunately the suspicions had not subsided and she was not allowed to return though she was given access to microfilmed material.

Stays in Barbados and Trinidad followed. There she worked as a freelance journalist for newspapers and radio and continued her efforts to write both fiction and non-fiction works. In Barbados she covered the Independence celebrations and produce among others a programme on the moves towards universal suffrage which aired on Independence Day. Radio Trinidad featured some of her writings on a programme called Monitor. It was during her time in Trinidad that she completed and in 1971 finally published her book Historic Heritage of St. Kitts, Nevis and Anguilla a small but comprehensive and well-illustrated encyclopaedia that covered a wide array of topics, from the Siege of Brimstone Hill to carnival queen shows. A comment in her Acknowledgements attests to the difficulties she experienced,

I appreciate the help of the many persons who assisted in checking the material. (I also include all “obstructionists,” who provided the grit in the oyster, producing this “pearl!”)

Manchester bore the cost of publication which she tried to recoup through the sale of advertising space in the book.

Confident in her own talent and undeterred by the lack of public interest, Manchester prepared other material for publication under the pseudonym of Kathleen Killikelly. Unfortunately it was not completed. As Miss Katie, dressed in traditional costume, Manchester entertained locals and foreign visitors and dignitaries with skits in Kittitian dialect and was often invited to perform at state functions but life as a freelance journalist, novelist and sometime teacher was far from lucrative.

Eric Skerrit, a successful businessman in St. Kitts who owned a copy of her book, quickly realised that the demand for it warranted a second printing. He even offered to pay for the printing of the first five hundred copies. Enthused at the prospect of her work being circulated again, Manchester returned to St. Kitts, not for a second printing but to write an update. She put all her energy into the undertaking and visited government departments, businesses, organisations and individuals with “painful persistence” to gather the required information and photographs for her new publication. However to many she had become a “bothersome” person who talked incessantly and she found it difficult to raise the much needed interest and support for her endeavour.

Misunderstood and unappreciated, Manchester’s last years were marked by increased bitterness. She continued to live alone in Sandy Point. Often in difficult financial circumstances, she could do nothing as portions of her work, the result of years of her research, were used wholesale in other publications and her authorship was never acknowledged. Still she plodded on hoping to re-publish her beloved Historic Heritage. Kathleen Manchester died alone at her home in Sandy Point on the 21st January 1992. Her friend, benefactor and old school mate, Agnes Skerrit rescued her from a pauper’s burial and started preparations for her funeral until other members of the community took charge.

Thomas Manchester

Thomas Manchester was born on the 16th August 1880. He was the sixth child and second son of James Thomas Allan Manchester and his wife Ann Catherine Atherton. A pillar of the St. Ann’s Anglican Church in Sandy Point, James was the owner of Lynch’s and New Guinea estates, the attorney for the Blake’s plantation and a member of the St. Kitts Executive Council. Together he and his wife had produced seven children, three boys and four girls.

After some years in Canada, where he studied construction engineering, young Tom returned to St. Kitts and took responsibility for running the family business. On the 14th January 1919, he married Ada Killikelly, the only daughter of the Rev, Charles Killikelly, Wesleyan Minister in Montserrat. Manchester had been on that island at the request of the Anglican community to supervise the rebuilding of the damaged edifices. They were married in the newly renovated church and the guests were a veritable who’s who of Kittitian and Montserratan society. The gifts of jewelry exchanged between the bride and groom were indicative of the wealth and social standing that they both enjoyed.

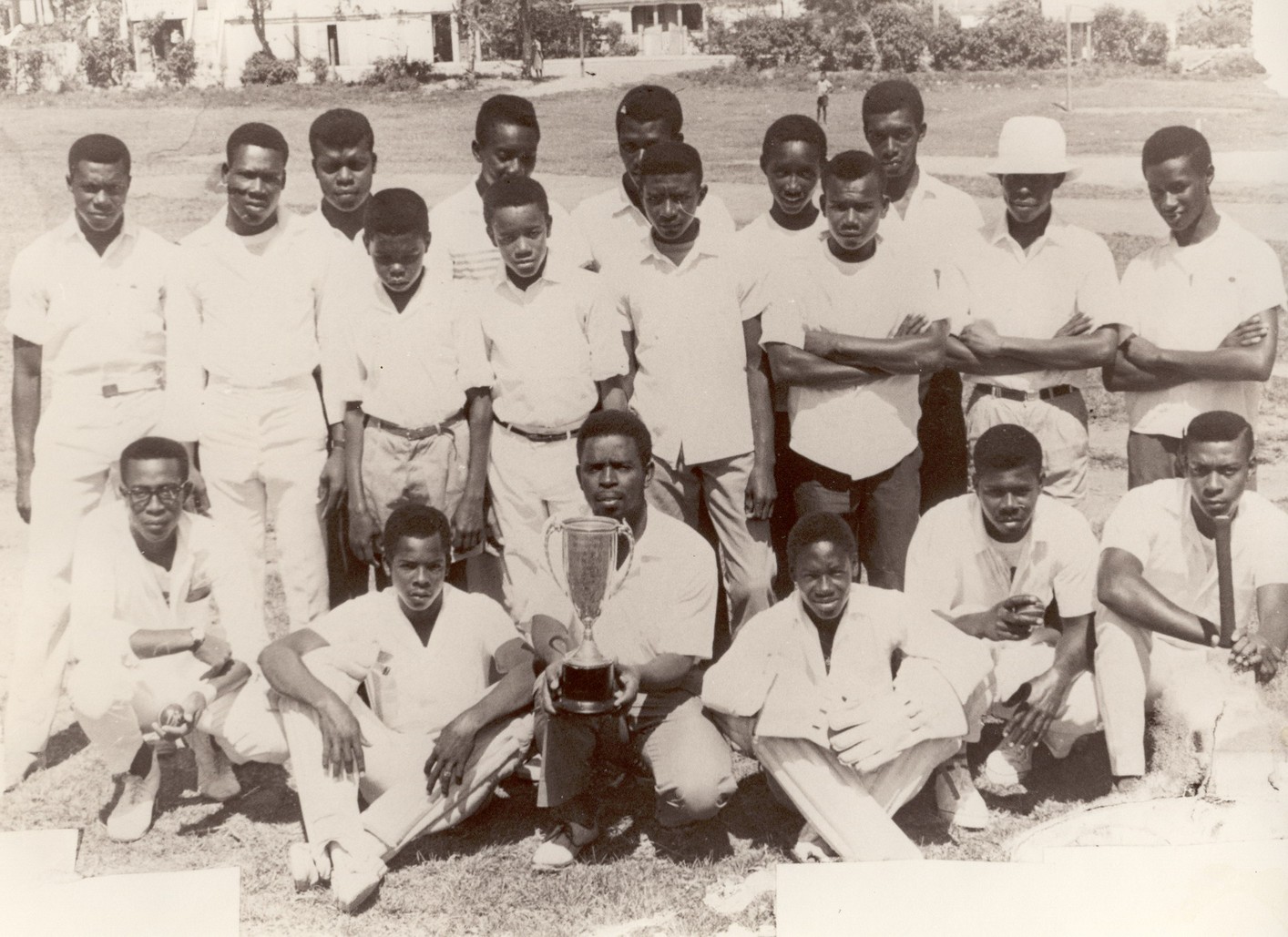

Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Manchester departed for St. Kitts two days after the ceremony. Their only daughter, Kathleen Dorothy, was born on the 4 th December 1923. Manchester ran Lynch’s Estate and managed New Guinea which was his sisters’ inheritance. He also opened a hardware and building materials store on his property at Main Street, Sandy Point. His community spirit ensured that his interest were more widespread and in 1923, on his initiative, the St. Ann’s Cricket Club was formed.

Within weeks of his return to St. Kitts, a fire threatened his home town in Sandy Point. The inefficiency of the Administration, the lack of social legislation and the poverty that surrounded him made a deep impression and drove him to take a stand in the community. In the St. Kitts-Nevis Daily Bulletin, he wrote: long before this fire occurred the attention of the government was drawn to the fact that a fire brigade with proper implements was imperative necessary for the protection of the town but as per usual the request was pigeonholed.

Expressing the concern of all property owners he remarked:

Old dilapidated huts are allowed to be placed immediately near cane fields adjoining the town of Sandy Point and in some instances cooking with open fires is being done inside, under or alongside these houses. Is there no law, Mr. Editor restricting the placing of houses within certain distances from cane fields adjoining the town of Sandy Point?

And after describing other poorly handled situations in Sandy Point, he concluded by asking: What is the good of a government that does so little to protect, and safeguard against destructive elements, the people whom it represents?

Ada died in 1928. She was only 38 years old. Grief stricken, and with a little daughter to maintain, Tom Manchester turned his attention to his work and to politics. Everyone in Sandy Point knew that Mr. Tom would lend a helping hand in difficult situations. Together with his friend, Alwyn Ribeiro, Manchester took up the cause of the sugar workers’ need for better wages.

Like his contemporaries in the region, Manchester became active in the campaign for elected representation in the Legislative Council. In 1922 he was one of the founding members of the St. Kitts Taxpayers Association. Its aim was to ensure efficiency and responsibility in government.

His activities on behalf of the disenfranchised aroused the resentment of the sugar baron. He sought the support of other men who understood the problem and were intelligent enough to articulate it and together, in 1932, they started the Workers’ League. On the 28th October of that same year, Manchester along with W.A.H. Seaton represented St. Kitts-Nevis at the West Indian Conference which met in Dominica to discuss the political future of the region.

The violence that erupted at Buckley’s in 1935 was not on the League’s agenda but having an understanding as to the underlying cause of the riots, the leaders were sympathetic and provided a means for some to escape to St. Eustatius, Saba and St. Barths and assisted others with legal representation in the trials that followed. They also realized that the frustration which had caused the outburst had to find a vent for escape through more disciplined activity. Manchester’s solution was the formation of a trade union. Following the passage of the law legalizing trade unions, he asked his cousin, Edgar Challenger to set up the St. Kitts-Nevis Trades and Labour Union.

In 1937 Thomas Manchester was elected a member of the Legislative Council as a Workers’ League candidate. He was re-elected in 1940 and also served as a member of the Executive Council for the Presidency of St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla and as a member of the Federal Executive Council for the Colony. An illness kept him out of circulation for nearly a year and on his return commented on the lack of caution that seemed to be making its appearance in the Legislative Council and even in the Movement he had helped found. The normally sympathetic Union Messenger of the 11th January 1941 took a critical view of Manchester’s political stance

We are in sympathy with the situation he (Manchester) is endeavoring to represent; but we must also admit that the tendency to great caution, which certainly has its advantages, and which, in this instance, seems to have reached the borderland of fear may be not unnaturally, the reaction to prolonged illness

The League was outgrowing its creator and beginning to see moderation as a fetter.

Manchester’s generous spirit and his whole-hearted devotion to the political issues he had embraced, caused him to neglect his business. As his debts rose, his creditors threatened to foreclose. His estate at Lynch’s was sold but that was not enough. His sisters sold New Guinea to help him out. He died soon after on the 31st January 1943 at the age of 52.

Lee L. Moore

Lee L. Moore was born on the 15th February 1939. He was the son of Daphne Moore of Half Way Tree and Theophilus Penny of Middle Island. Miss Moore was a maid and Lee was her only son. His introduction to school life came through a kindergarten in Half Way Tree run by Mavis White. At five years of age he entered the Middle Island Government School. Life for mother and son was relatively comfortable until the day when the trash house they lived in at Godwin Ghaut burnt down. They moved into a rented wooden house and the financial situation became strained. Lee was then eight years of age.

In 1952 he won a Government Scholarship to the St. Kitts-Nevis Grammar School. It covered all his expenses except uniforms and games fees and although the situation was far from easy, Miss Moore was determined that her son would not lose this opportunity to gain an education. Soon after he found himself attracted to the Gospel Hall and became very much involved in the branch at Middle Island. Members of the church described the teenager as the “Wonder Boy Preacher,” or “the little boy with the Big Bible.” By age 14, Moore was teaching a Sunday School class. He organised hikes for young people in his village on public holidays and taught mathematics at evening classes for members of the Sunday School.

Five years later, young Moore was the recipient of the Leeward Islands Scholarship. Many had hoped that he would have pursued studies in medicine but he did not see himself as a doctor and he chose instead to follow a career in Law. He was accepted at the University of London, King’s College. During the summer vacation he worked at the London Stock Exchange in order to supplement his income. After a short stay in university lodgings, young Moore decided to move in with his mother who had married and moved to England. The family hoped that when the allowance from his scholarship was combined with the income made by his mother and stepfather, life for all three would have been made less difficult.

His oratorical skills made him Intervarsity Debating Champion for two consecutive years. In 1962 he graduated with an LL.B. upper second class honours and he also obtained a Diploma in Theology. He was awarded the Jelf Medal in the Faculty of Law and qualified as an Associate of King’s College. One year later, Lee Moore took his Master’s degree and was admitted to the Inner Bar of the Honourable Society of Middle Temple. After further research he took up the post as Lecturer in Law at the City of Birmingham, College of Commerce later renamed the University of Central England. As member of the diaspora in the United Kingdom, Moore witnessed the discrimination suffered by non-British residents. Thus he gravitated to the Council Against Racial Discrimination Moore had also intended at that time to pursue a Ph.D. on the subject, Land Laws of the Caribbean which he felt would have been the defining point in his career. But events in the Caribbean caused a change of plans.

In 1967 St. Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla embarked on the stormy road of Statehood in Association with Great Britain. The international image of the new state was tarnished from the outset by the Anguilla crisis. An effort to recruit promising young men was launched by Fitzroy Bryant. Moore was one of the persons approached. His response was, at first, cautious. However realising how much his talent and energy were required by the emerging nation, Moore quit his well paid, comfortable job in England and returned to St. Kitts, to serve as Public Relations Officer to the Premier. Governor, Sir Fred Phillip, recruited him to teach Law of Tort at his law classes at Government House. He set up his own private law practice and on the political front he threw his lot in with Young Labour which was just emerging as a vigorous branch of the St. Kitts-Nevis Labour Party.

His legal prowess was immediately recognised when in 1967 he defended the implementation of the National Emergency Powers and then successfully argued the legality of those actions before the Privy Council. In 1969 he was appointed counsel to The Wooding Commission which investigated the Anguilla affair. The following year he was appointed Counsel to the Commission which enquired into the Christena disaster.

In 1971, he contested his first election in the new State, running in electoral division number 4 which then included the area from Old Road to Sandy Point East. He beat William Herbert, founder-president of The People’s Action Movement by 826 votes to 682. Moore was one of three new members of the Labour team that emerged victorious in that year’s election. Premier Bradshaw appointed him Attorney General and Minister of Legal Affairs a position he held until 1979.

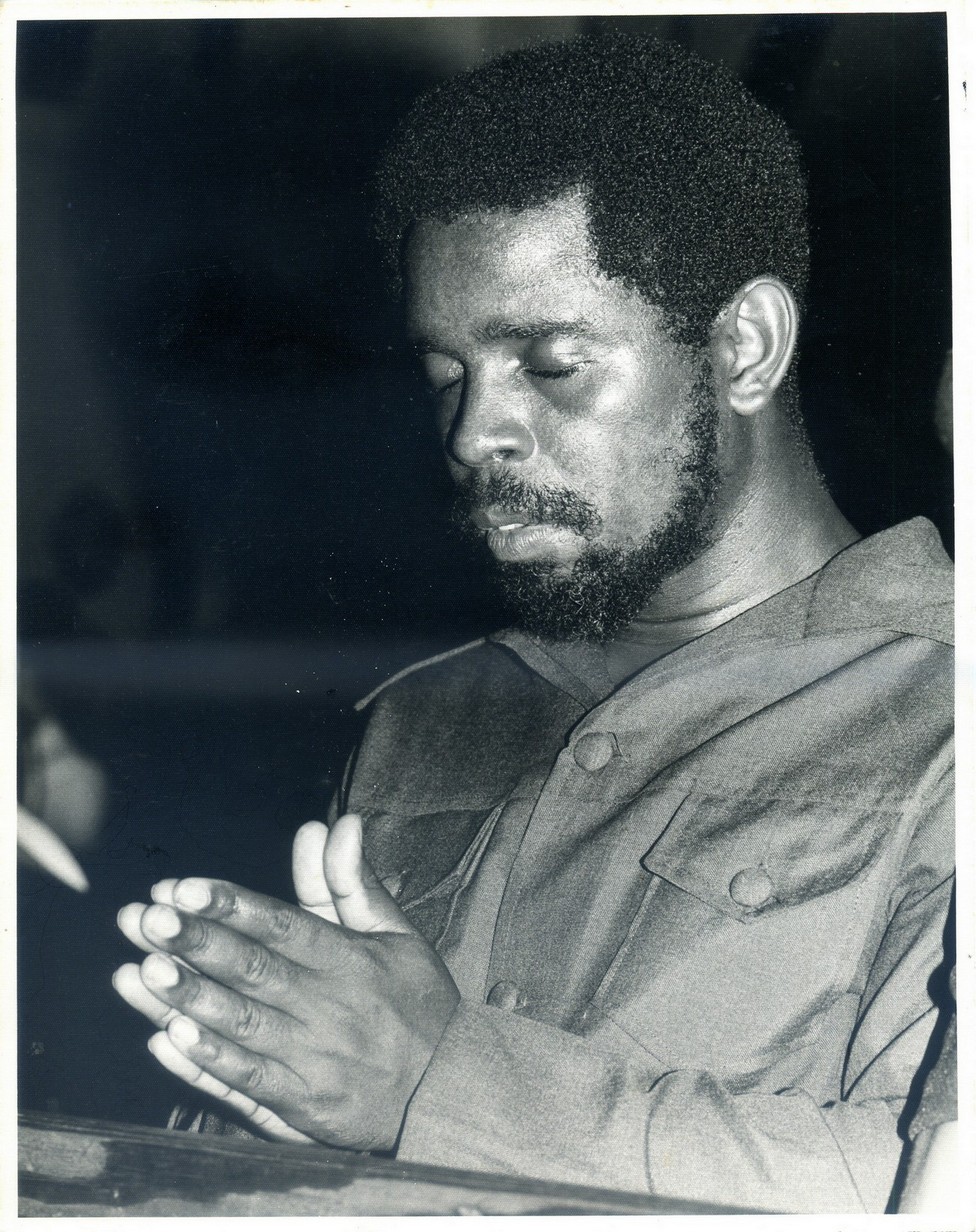

He stomped onto the political platform with a determination to serve his country “As Jesus said, ‘Man was not made for the Sabbath but the Sabbath for man’ so I tell you tonight that the people of this country were not created for the Constitution but the Constitution for the people. The Constitution will be servant not master in this country...” And he was willing to do so despite the disapproval of the opposition, “Who want peace, here’s peace, who want love here’s love, who want friendship, here’s friendship but who don’t want it brother, here’s power.” His outspoken statements on the political platform did little to endear him with certain sections of the general public and made him instead a target for the opposition’s attacks on the Party.

However The Labour Spokesman described Moore as “a specialist in his field who knows the laws of the game like the palm of his hand - the Clive Lloyd of the team.” It was precisely this knowledge of the law that stood him in good stead when he became involved in the negotiations and the drafting of legal instruments that resulted in a second attempt to unify the Caribbean. In 1973 the Treaty of Chaguaramas was signed launching the Caribbean Community and Common Market. He was also integrally involved in the creation of the Treaty of Basseterre which brought into being the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States in 1981.

Lee Moore was to serve as Parliamentary representative for Constituency No. 4 up to 1984. He also served as second vice president of the St. Kitts-Nevis trades and Labour Union. Following the death of Comrade Bradshaw in 1978, Moore succeeded him as President of the Union.

His tenure as Attorney General was coloured by three cherished principles, the empowerment of the masses, integrity and good governance and individual rights. It was the first of these that Moore saw come into effect when the sugar lands were acquired in 1975. When the matter was contested in Court he channeled all his energy into defending the government’s position because he understood the greater benefit to the community that resulted from the passing of the Act. It was to his credit that when a case in court involved the State, he handled the matter personally.

When Premier Paul Southwell died in St. Lucia on the 18th May 1979, Lee Moore was with him. They were part of the delegation that was preparing the groundwork for the Treaty of Basseterre. As leader of the Party, Moore was immediately called upon to form the new government

The first few weeks of the new administration were fraught with controversy over Premier Southwell’s sudden passing, and Moore found himself the target of malicious rumours. In an address that chronicled the events and investigations following the Premier’s death, Moore declared, “I have never cherished any fear of any revelation because before God and man I have always known that my hands are clean.”

However it was with a spirit of optimism and hope that Moore greeted the new decade. Whilst emphasising the need for respect, hard work, and the setting of priorities he went on to declare “that before midway through this year we shall be a full sovereign and independent country.” To ensure that his policies for the new nation would have a broad base, he started 1980 with a consultation on Development Strategy to which were invited persons in both the private and public sector of the economy all of whom he hoped would be “involved in moving the country forward.”

But looming over the political path that Moore was trying to lay, was the matter of the seat in Central Basseterre, vacated by the death of Premier Bradshaw. Although the bye-election had returned Anthony Ribiero as representative for that constituency , a court case brought by Dr. Kennedy Simmonds the PAM representative had produced a reversal of the electorate’s decision. Whilst the Court of Appeal did not agree with the Judge’s course of action in the matter, it neither reversed the decision nor did it nullify the election. Added to this was the matter of a new by-election to fill the seat in Constituency no.1. With elections constitutionally due by the end of the year, Moore decided to go to the electorate and ask for a clear mandate for his administration.

The General Election of 18th February 1980 saw the majority votes being cast for the Labour Party but only four party candidates were actually elected. The remaining seats in St. Kitts went to the People’s Action Movement which quickly entered into a coalition with the Nevis Reformation Party and formed the new government. Lee Moore became the leader of the Opposition. The marriage of convenience was not expected to last long but Labour underestimated the willingness of the PAM leadership to compromise with NRP to maintain power. It was a compromise that was to find itself written into the new Independence Constitution. While Moore and Labour advocated separate local government for the two islands with an overall Federal Government, the new constitution gave Nevis alone its own local government and a right to secede.

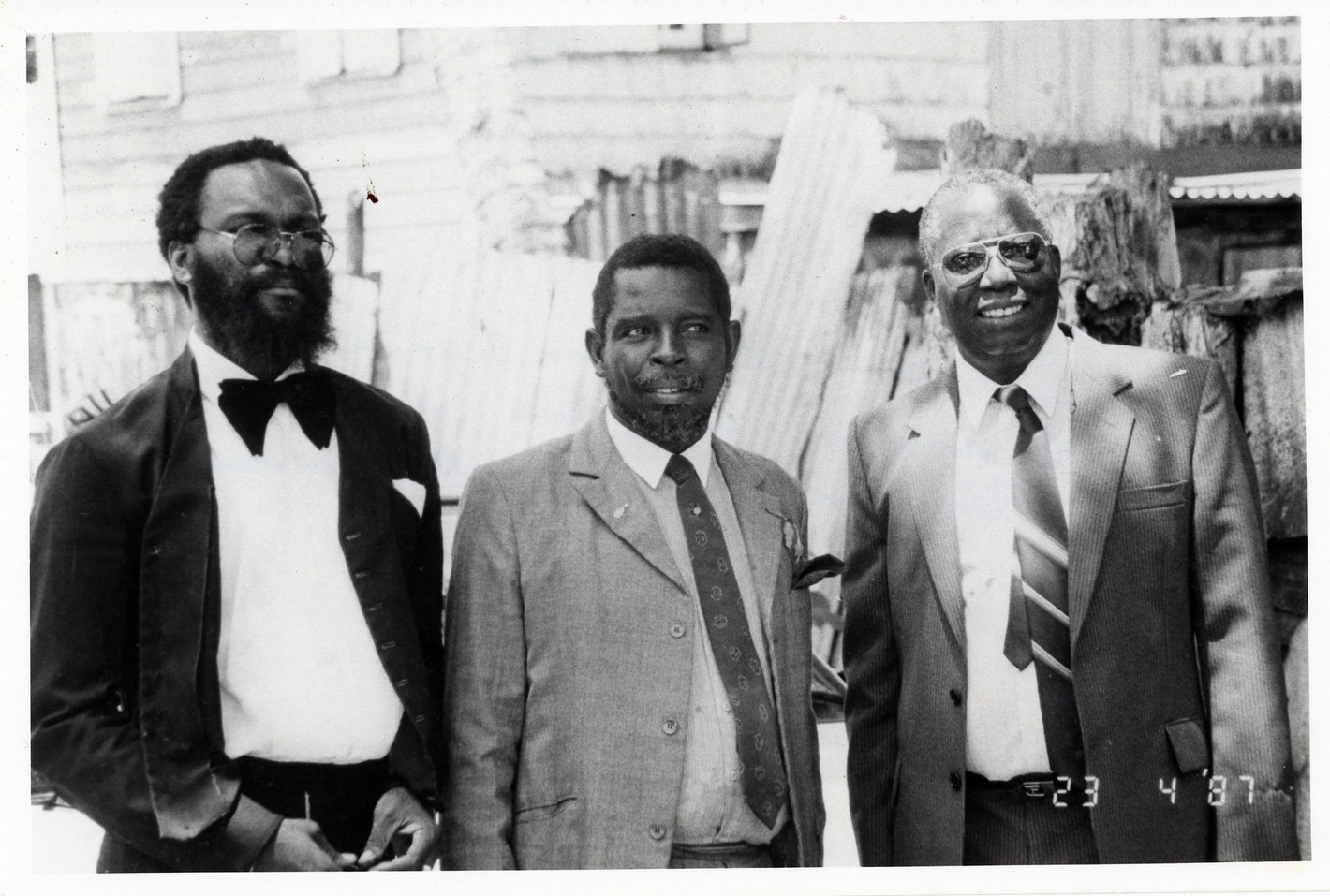

The debate on the Independence Constitution was a heated one and Moore’s comrades Fitzroy Bryant and Fidel O’Flaherty found themselves brought before the court on charges of incitement and sedition because of statements made in political meetings. O’Flaherty faced a number of other charges in Magistrate Court arising out of a situation in a “Meet the People” meeting in New Town. Although he had been critical of Moore’s leadership, O’Flaherty still received the best defense that the party leader and his associates, C Fitzroy Bryant and Henry Browne could give. When in 1987, it was Moore’s turn to face trial again on charges of incitement and sedition, local lawyers and those from Antigua were present in the court room to show their support for him.

The years immediately after Independence saw a shift in the sphere of activity. Whilst still making his point at every opportunity in the House of Assembly, Moore and his party took their message to the towns and villages of St. Kitts with weekly public meetings. The courtroom became, from time to time, a testing ground in which individual constitutional rights were contested.

The 1984 election cost Lee Moore his seat in Parliament. His second defeat came in 1989 and this was followed soon after by a division of leadership within the Labour Movement. Whilst he maintained the Presidency of the Trades and Labour Union, leadership of the Party passed into the hands of Denzil Douglas, then a relative new comer on the political scene.

Moore’s untiring defence of his clients had become well-known in St. Kitts. The political affiliation of the person he represented was of no consequence to him. He merely saw before him a person entitled to the best defence under the law. In this respect he was even willing to work with political rivals to ensure that his clients were properly represented. Throughout his legal career, Moore worked constantly and consistently for many union members who had pending legal matters and were unable to pay fees and in more recent years he often offered his services free of charge to persons who appeared in court without a defence counsel.

A further recognition of Moore the jurist, came in 1993 when he was chosen as Senior Counsel to the Commission of Inquiry into the Sir Lynden Pindling Administration in the Bahamas. He played a similar role again in 1997 when the Williams Commission was set up to enquire into the activities of the PAM administration in St. Kitts.

Following the Labour victory of 1995, Lee L. Moore was appointed Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary non-resident Permanent Representative to the United Nations. In this new role he was responsible for advising Government with regards to the ratification of treaties and conventions and with regards to its position vis a vis other countries and the UN. It was in this capacity that he was able to establish diplomatic relations with South Africa in 1998. He was also a member of a two-person commission to study closer political integration between Barbados and the member countries of the OECS.

In September 1999, Moore left St. Kitts for New York where he underwent medical treatment. Sir Lee Llewellyn Moore, KCMG, QC, LL,M died as a result of his illness on the 6th May 2000. He left his mark in St. Kitts and the wider Caribbean through his scholastic abilities, his extraordinary oratorical skills, his devotion to his country and his commitment to regional integration.

Joseph Alexander Nathan

Joseph Alexander Nathan was born on the 28th February 1881 to Joseph Nathan a butcher in Irish Town and his wife Alice nee Brisco. He was to become the most militant of the union organisers.

In October 1896 he had applied to the government for a certificate of nationality, migrating to the US soon after. He returned to St. Kitts sometime before 1912 and entered the retail trade, establishing a small business which he called The International Supply Association.

He was strongly anti-colonial in his outlook and was described by the authorities as ‘waster and a pro-German.” He was in fact an admirer of German militarism and efficiency. With the First World War raging in Europe, such an attitude was not at all popular with the Colonial Authorities.

In 1916 the St. Kitts Universal Benevolent Association was launched and Nathan was its secretary. Before the public, the UBA was an organization aimed at providing benefits for its members. However it was also involved in labour agitation directed in particular against the Masters and Servants Act of 1849. On the 3 October 1917, Nathan wrote a letter on behalf of the UBA requesting its repeal. Following the passing of the Trade and Labour Union (Prohibition) Ordinance no. 9 of 1916, Nathan was able to smuggle out a letter to Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of Labor enclosing a copy of the ordinance appealing to Gompers to use his influence in support of the working class of the Presidency and to bring the issue to the attention of the British “Federation of Labour” and the Secretary of State for the colonies. Gompers informed the Secretary of the TUC on the matter and a question on the Ordinance was raised in Parliament. Trade Union circles in England raised a flood of protests on the matter.

After Solomon’s death and the election of Sebastian as President, Nathan found himself isolated. Sebastian’s moderate approach to politics limited the UBA’s activities to those of a purely benefit society. The new President’s priority was the running of the newspaper. Nathan was left to, almost single-handedly, run the organization. He devoted his attention to achieving a growth in membership but, as neither the government nor the employers would recognize it as a bargaining agent for workers, the number of members of the UBA declined drastically.

In 1932, the Worker’s League was founded and Joseph Nathan was a member of its Executive Council. Three years later he launched another attempt to revive the UBA among estate workers. He invited head cutters and head cart men on the various estates to attend a meeting to discuss wages for the reaping of the 1935 crop. According to Nathan’s report of the meeting, the participants agreed that the UBA should represent them on matters of wages and working conditions. However, he advised the gathering that since there would be no increase in the price of cane that year, wages offered should be accepted. Sections of the meeting left in disappointment. Nathan’s sense of caution left him, and the UBA, without a following. The authorities however saw him as the instigator of the riots.

Two years later the Workers’ League contested the first election in sixty years. Nathan remained in the background and demonstrated his dissatisfaction by stating that neither candidate seemed to be seriously talking about organised labour and increased wages. In 1939, following the passing of the Trade Union Act, Nathan again attempted to form a trade union. On the 6th February of that year he wrote to the administration appealing for a grant of £300 for the purpose of organising a trades and labour union in the presidency. The Executive Council unanimously rejected his request.

In 1940 Nathan was charged with making a public statement about the war intended to cause despondency. He was found guilty and sentenced to pay a fine of £2 or serve 21 days in prison. He chose to pay the fine.

In 1943 Joseph Nathan suffered a stroke from which he recovered enough to enable himself to move around town although with some difficulty. Another stroke, however ended his life on 11 August 1948. He died at his home in College Street and was survived by four children.

Sir Milton Allen

Sir Milton Pentonville Allen was born at Palmetto Point on the 22 nd June 1888. He was the son of Daniel Allen a stone mason of Challengers and Henrietta Garvey. He received his early education at the Methodist school in his village. Although he had academic potential, young Milton preferred a trade to teaching, much to the disappointment of his teacher Miss Geraldine Locker. He was therefore apprenticed to a tailor in Basseterre and then emigrated to the United States in search of a better future. In the United States he took his trade seriously and graduated with a diploma from the David Mitchell’s Cutting and Designing School.

While in New York he kept an eye on developments at home and was inspired at the thought of an organization that would promote workers’ rights. In a letter to the editor of the Union Messenger, published on the 31 st December 1931, he wrote, The time has come and devolves most imperatively upon the inhabitants to join forces in defense of those rights. Of course it is understood that the larger your organization the greater will be your financial obligations. But you would be within your rights to call upon West Indians abroad to assist in this arduous, but righteous effort.

True to his word, Allen became part of concerned group of Kittitians who sent financial assistance to the Workers’ League when it was founded. Following the Labour disturbances of 1935 they sent support which made it possible for the League to assist those accused of rioting to obtain legal representation. In 1935 after more than twenty five years in the United States, Allen was back in St. Kitts and resident in Sandy Point. He showed himself to be an ardent supporter of Thomas Manchester and even appeared as a speaker on the League’s platform.

In 1937 after almost two years in St. Kitts, he married Annie Locker, Head Teacher at the Sandy Point Girls’ School and the couple returned to New York. When she returned to her post, he supported the school’s extra-curricular activities by sending her much needed sheet music. He wrote poetry and even published a collection of poems one of which was set to music for choir by Dr. Leon Forrester, a musical examiner of the Royal College of Music in London, England. From time to time he contributed items to The Un ion Messenger often expressing concerns regarding the well-being of workers. Once in St. Kitts his connection with the newspaper world became more significant as he became associate editor of the Workers’ Weekly and the Union Messenger and later editor of the Labour Spokesman.

Allen retired and returned to St. Kitts in the 1950s and turned his attention to the service of the public through the Workers League. A quiet unassuming man, Allen also had a strong sense of dignity and decorum. Austin Eddie remembered that when Robert Bradshaw called out the masses to protest the appointment and arrival of Governor Blackburne, Allen was the only person in the League to chastise the labour leader for the vulgar behaviour he had encouraged. He was a member of the Legislative Council from 1958 to 1962 and served as minister without portfolio. That year saw the termination of the West Indies Federation and the return of Robert Bradshaw to St. Kitts. Allen resigned his seat so that Bradshaw could return to the Legislative Council. On the 27th August 1966, he was appointed Speaker of the House of Assembly.

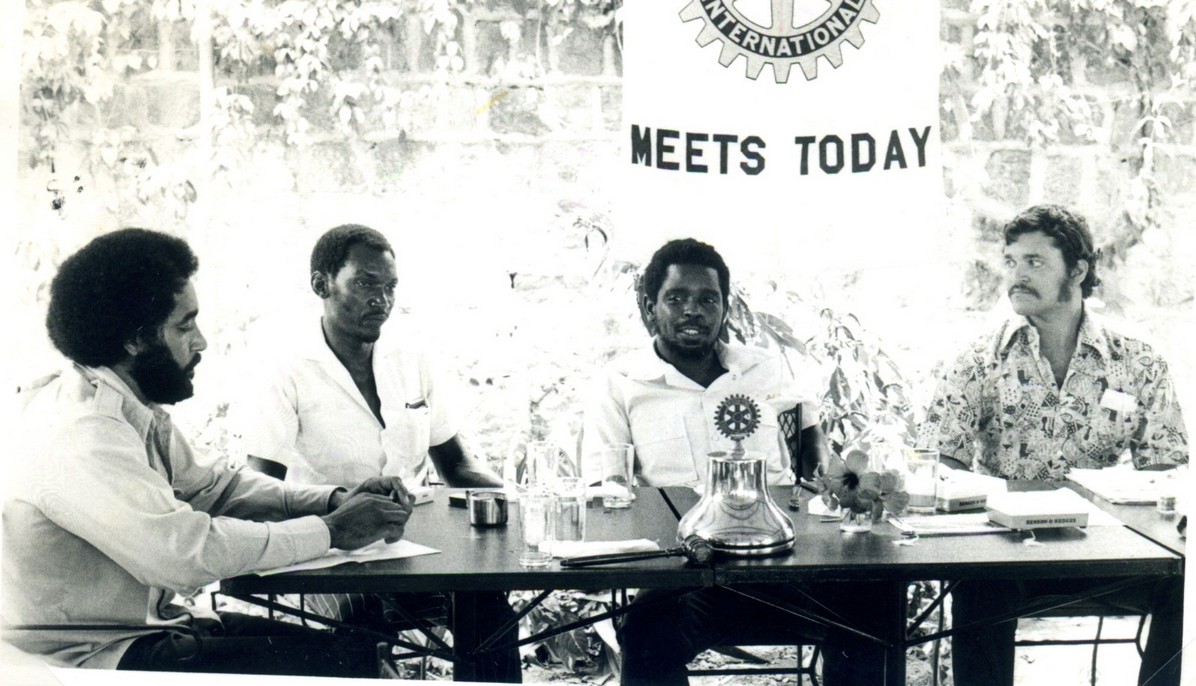

In 1969, Milton Allen became the first native of St. Kitts to be appointed Governor of the Associated State of St. Kitts, Nevis and Anguilla, a post he continued to hold till his retirement in 1975. He performed the duties of his post with honour and integrity. He also fulfilled the duties of Chief Scout, Patron of the St. John’s Ambulance Brigade, Member of the Conservation Society for Historic Sites, Honorary life member of the Rotary Club. He also remained a member of the Methodist Church.

Sir Milton Allen died at the J. N. France General Hospital on the 17 th September 1981.

National Archives

Government Headquarters

Church Street

Basseterre

St. Kitts, West Indies

Tel: 869-467-1422 | 869-467-1208

Email: NationalArchives@gov.kn

Website: www.nationalarchives.gov.kn

Follow Us on Instagram